The next morning, I was relieved to be soon departing Cienfuegos, but had a lot of trouble finding any vehicle to take me back to Havana. I went to three different travel agencies, the sole bus station – there was none for foreigners in the city – and finally to the main taxi depot. There I was able to secure a ride; the driver wanted 60 Euros but I said I only had 40 (which I thought at the time was plenty, but soon realized how far was the distance) and the driver agreed.

Euros and dollars are extremely attractive to Cubans, for with the currency they can buy scarce or otherwise unobtainable items at special “MLC” stores in Havana. (MLC an acronym fo “moneda libre convertible”. The stores were an innovation announced in mid-2020; most Cubans quickly showed hatred for the divisive concept.)

The mid-afternoon trip in a standard yellow cab (thankfully with seat belts!) lasted almost three hours and my taxi driver was laconic or non-responsive, so I had plenty of time to enjoy the scenery: vast fields of sugar cane at the outset, while the roads were pock-marked (I learned a new Spanish word: baches – pot holes); and, as we got closer to Havana the road became improbably wide, able to accommodate some six lanes of traffic; yet there were few vehicles. Hedges separating oncoming traffic flow for many miles had been trimmed into large, flat shapes, which provided a pill-box appearance.

I returned to the Havana casa particular I had stayed in before and was welcomed by one of the women, Sra. Leonarda, pleased to hear of some of my travel experiences. I went out shortly thereafter, determined to find a good wi-fi signal location, ultimately ending up some 10 blocks away at a small, sparse park near a large hotel on the other side of the main promenade, El Malecón. By this time, it was dusk. The neighborhood was rough but no one bothered me as I sat on a bench with my Apple MacBook Pro laptop, frenetically pecking away as I tried to catch up on messages before the battery died.

Returning to the casa was interesting, as I took a different route and through the very gritty streets of El Centro. I saw strings of overhead lights down one street and took a photo of a scene including an antique car which attracted me. Turning around, I looked through the window of the building and was amazed to see inside was what looked like a well-appointed restaurant. I entered the building and discovered an ambience with table cloths and embroidered napkins which could have been appropriate for a five-star eatery in Miami or Paris. I found a couple of items on the menu – rice pilaf and broiled potatoes – and treated myself to a mojito and a banana dessert topped in glazed sugar as well. Talking with the waitstaff and then the owner, I learned that the restaurant had recently re-opened after more than a year of closing since the pandemic began. Cost of my meal was just $11. En route back to my casa, through the dim streets teeming with loving, ebullient, petulant, patient souls, I began composing a poem, which I finished shortly thereafter:

Wɪᴢᴇɴᴇᴅ

𝗔𝘁 𝗻𝗶𝗴𝗵𝘁

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗳𝗮𝗰𝗲𝘀 𝗮𝗽𝗽𝗲𝗮𝗿

𝗜𝗻 𝗰𝗿𝘂𝘀𝘁𝗲𝗱 𝘄𝗶𝗻𝗱𝗼𝘄𝘀

𝗦𝗲𝗲𝗸𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗔𝗻𝗼𝘁𝗵𝗲𝗿

𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗹𝗮𝘂𝗴𝗵𝘁𝗲𝗿

𝗟𝗶𝗳𝘁𝘀

𝘁𝗵𝗮𝘁 𝗰𝗿𝗲𝗮𝗸 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗴𝗿𝗼𝗮𝗻

𝗳𝗼𝗿 𝘁𝗵𝗲𝗿𝗲 𝗶𝘀 𝗻𝗼 𝗴𝗿𝗲𝗮𝘀𝗲

𝘁𝗼 𝗵𝗲𝗹𝗽 𝘁𝗵𝗲𝗺

𝗯𝘂𝘁 𝘆𝗲𝘁 𝘀𝘁𝗶𝗹𝗹 𝘁𝗵𝗲𝘆 𝗿𝗶𝘀𝗲, 𝗱𝗮𝗿𝗸 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗺𝗼𝗼𝗱𝘆

𝗮𝘄𝗮𝗶𝘁𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗔𝗻𝗼𝘁𝗵𝗲𝗿

𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗱𝗮𝘆𝗹𝗶𝗴𝗵𝘁

𝗦𝗰𝗲𝗻𝘁𝘀! 𝘀𝗺𝗲𝗹𝗹𝘀! 𝘀𝘁𝗲𝗻𝗰𝗵!

𝗴𝗹𝗶𝗱𝗲 𝗯𝘆 𝗺𝗲

𝗮𝘀 𝗳𝗶𝗴𝗵𝘁𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗳𝗲𝗹𝗶𝗻𝗲𝘀 𝗽𝗮𝘂𝘀𝗲

𝗯𝗮𝗹𝗮𝗻𝗰𝗲𝗱 𝗯𝗲𝘁𝘄𝗲𝗲𝗻 𝗳𝗹𝗶𝗴𝗵𝘁 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝘁𝗵𝗶𝗿𝘀𝘁

𝘁𝗵𝗲𝘆 𝗮𝗿𝗲 𝗯𝗲𝘆𝗼𝗻𝗱 𝗺𝗲

𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗜 𝗴𝗿𝗶𝗲𝘃𝗲

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝘄𝗼𝗺𝗲𝗻 𝘄𝗮𝗹𝗸 𝘄𝗶𝘁𝗵 𝗺𝗲

𝗳𝗼𝗿 𝗮 𝗵𝗮𝗹𝗳-𝘀𝘁𝗲𝗽

𝗮𝘀 𝘁𝗵𝗲𝘆 𝘀𝗵𝗮𝗿𝗲 𝘄𝗶𝘁𝗵 𝗲𝗮𝗰𝗵 𝗼𝘁𝗵𝗲𝗿 𝗴𝗹𝗮𝗱 𝗵𝗼𝗽𝗲𝘀

𝗹𝗼𝘀𝘁 𝗹𝗼𝘃𝗲𝘀, 𝘁𝗲𝗮𝗿𝘀,

𝗼𝗿 𝗺𝗶𝗺𝗶𝗰 𝘀𝗼𝗻𝗴𝘀

𝗙𝗿𝗼𝗺 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗯𝗹𝗲𝗮𝗸 𝗯𝗼𝗱𝗲𝗴𝗮

𝗜𝗻 𝗯𝗶𝗻𝘀 𝗼𝗳 𝗯𝗼𝗻𝗶𝗮𝘁𝗼

𝗛𝗮𝘃𝗮𝗻𝗮 𝗳𝗶𝗻𝗱𝘀 𝘀𝘂𝘀𝘁𝗲𝗻𝗮𝗻𝗰𝗲

𝗴𝗿𝗶𝗺𝘆 𝗴𝘂𝘁𝘁𝗲𝗱 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗴𝗻𝗮𝘀𝗵𝗲𝗱

𝘁𝗵𝗶𝘀 𝙗𝙤𝙘𝙖𝙙𝙞𝙩𝙤 𝗽𝗹𝗮𝗶𝗻 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗱𝗿𝘆

𝘁𝗵𝗶𝘀 𝗱𝗮𝗿𝗸 𝗽𝗲𝗲𝗹 𝘄𝗶𝘁𝗵 𝗹𝗶𝗳𝗲 𝗶𝗻𝘀𝗶𝗱𝗲!

𝗛𝗮𝘃𝗮𝗻𝗮 𝗵𝗮𝘀 𝗻𝗼𝘁 𝗹𝗲𝗳𝘁

𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗮𝗻𝗰𝗶𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗱𝗮𝘆𝘀

𝘁𝗵𝗲𝘆 𝗮𝗿𝗲 𝗵𝗲𝗿𝗲: 𝗶𝗻 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝘄𝗮𝗹𝗹𝘀 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝘄𝗼𝗼𝗱

𝘄𝗵𝗲𝗿𝗲 𝘄𝗲 𝗳𝗶𝗻𝗱 𝘄𝗮𝗻𝘁𝘀 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝘄𝗼𝗿𝗿𝗶𝗲𝘀

𝗮 𝘃𝗶𝗰𝘁𝗼𝗿𝘆 𝗿𝗲𝗳𝘂𝘀𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝘁𝗼 𝘃𝗮𝗻𝗶𝘀𝗵

𝗮𝘀 𝘄𝗶𝗰𝗸𝗲𝗱 𝗼𝗻𝗲𝘀 𝘄𝗼𝘂𝗹𝗱 𝗵𝗼𝗽𝗲

𝗛𝗮𝘃𝗮𝗻𝗮 𝗱𝗮𝗿𝗲 𝗻𝗼𝘁 𝗹𝗼𝗼𝗸 𝗯𝗲𝘆𝗼𝗻𝗱

𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗮𝗯𝘀𝗲𝗻𝘁 𝗺𝗶𝗹𝗸 𝗼𝗿 𝘀𝗼𝗮𝗽

𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗱𝗮𝗺𝗻𝗲𝗱 𝗱𝗼𝗹𝗹𝗮𝗿 𝘀𝗼 𝗯𝗿𝗶𝗴𝗵𝘁

𝗯𝘂𝘁 𝗶𝗻 𝗱𝗮𝗿𝗸𝗻𝗲𝘀𝘀

𝘀𝗼 𝗛𝗮𝘃𝗮𝗻𝗮 𝗴𝗮𝘁𝗵𝗲𝗿𝘀 𝗵𝗲𝗿 𝗿𝗼𝗯𝗲𝘀

𝘀𝗼𝗼𝘁𝘆 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝘀𝗼𝗮𝗸𝗲𝗱

𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝗲𝗮𝘁𝘀 𝘁𝗶𝗺𝗲 𝗮𝘀 𝗵𝗲𝗿 𝗲𝘀𝘀𝗲𝗻𝗰𝗲.

• • •

The next morning, December 16, after an early breakfast and walking through the Havana streets to photograph people up close with my telephoto lens for a photographic essay I envisioned (“Cuba in the COVID Era”), I packed for my next destination. I had left one of my pieces of luggage at the casa during my prior trips and now pulled out and bagged up the final food and medicine items I wanted to donate to the needy. I had arranged to be picked up by a driver named Humberto, to take me to the nearby town of Abel Santamaria. The vehicle I rode in was a 1954 Wilson truck (“No model name – just Wilson,” Humberto said). With no seat belts and sparse horsepower, we threaded our way slowly in the brilliant sun away from the noisome Havana traffic, as I tried in vain to not inhale oncoming diesel fumes.

Our destination is named after one of the heroes of Fidel’s first and failed attempt at overthrowing the Batista regime in 1953. The town was some ten miles distant from the entry point to the San Lazaro Church pilgrimage path. The casa particular I was to stay in was arranged by the maid of my Havana casa, as she had contacts.

I was met by Sra. Mare Elena, a round and happy woman pensioner, and settled into a dingy and sparse room, soon cramped by my three large bags and two smaller ones. The day still offered some light and I wanted to walk around the neighborhood a bit to photograph. This casa was next to a small power substation. A few doors down was a primary school, and I arrived just as the students were being released. Dozens of parents waited in front of a gate, and the reunions were surprisingly emotional. I raised my camera and took a few photos.  One teacher came outside of the gate and asked me what I was doing. I said I was a tourist, and she said, “Ah, está bien,” so I continued photographing. Suddenly another woman emerged and angrily confronted me. She had one eye clouded over, was perhaps partly blind, but she demanded to see my camera and the photos. I held out my camera to display one of my wide-angle shots. She exclaimed, “This won’t do!” and loudly excoriated me. “Would you let me photograph your children outside of their school?” I said, “Of course!” This only made her furious, so I said, “No problem, I will stop and leave; sorry!” I cautiously departed and then quickly left the scene, returning to my quarters.

One teacher came outside of the gate and asked me what I was doing. I said I was a tourist, and she said, “Ah, está bien,” so I continued photographing. Suddenly another woman emerged and angrily confronted me. She had one eye clouded over, was perhaps partly blind, but she demanded to see my camera and the photos. I held out my camera to display one of my wide-angle shots. She exclaimed, “This won’t do!” and loudly excoriated me. “Would you let me photograph your children outside of their school?” I said, “Of course!” This only made her furious, so I said, “No problem, I will stop and leave; sorry!” I cautiously departed and then quickly left the scene, returning to my quarters.

Later, Doña Mare laughed about the incident and ridiculed the school director, saying insulting things about her and that I was perfectly within my rights to be outside taking a few photos. I enjoyed a room-cooked dinner, where I consumed the last beans and rice I had brought to Cuba and then ceremoniously disposed of the exhausted Sterno can. I tried to sleep that evening, but was perturbed by the incessant barking of a dog just outside my windows.

The next morning, I inquired about the dog. His name is Mocho and I soon discovered he was spending all of his life stuck inside a stout cement and rebar cell in the back yard, surrounded by his own filth. Doña Mare said his function was to be a guard dog, and she claimed he would hurt the chickens in the yard if he were to be let loose. I went out after breakfast into the stinking yard and tried to soothe the dog, who, at first growled at me, then allowed me to touch his snout through the bars. Here was true suffering, and I resolved to do something about it. But I had to be diplomatic and patient, for I didn’t want to get kicked out of my casa for overstepping any social boundaries.

I had all morning to catch up on my journaling and editing photos, but when Mocho’s barking became too much to bear, my patience wore thin. I went down to inquire about whether there was a leash and collar and could I walk Mocho. Doña Mare said his head was “too small” for a collar and he would slip out. I asked if I could devise some harness to put around his body, and she seemed agreeable.

I returned to my room to conjure up some system over the next half hour and was able to cannibalize my backpack for one of the three straps, and found a long cloth ribbon I had been saving for years in my tool kit. Doña Mare’s adult son and I soon attached the harness to Mocho. The son tried it out and over the next hour I was gratified see the dog enjoy what surely must have been his first walk. At first, Mocho was confused and hesitant, but soon got the hang of things, as we walked in a small area in front of the house (I dared not go out in the street for fear of running into the school director!) I hoped this happy experience would be just the first of many for the hapless dog.

I returned to my room to conjure up some system over the next half hour and was able to cannibalize my backpack for one of the three straps, and found a long cloth ribbon I had been saving for years in my tool kit. Doña Mare’s adult son and I soon attached the harness to Mocho. The son tried it out and over the next hour I was gratified see the dog enjoy what surely must have been his first walk. At first, Mocho was confused and hesitant, but soon got the hang of things, as we walked in a small area in front of the house (I dared not go out in the street for fear of running into the school director!) I hoped this happy experience would be just the first of many for the hapless dog.

In the early afternoon, the son drove me in his car some ten miles to the entry point for the Pilgrimage of San Lazaro. We had to drive past the airport, Havana’s José Martí International. I arranged for the son to pick me up at 6:30 p.m. and exited to start walking into the sun from the road entry point. The road to the church was closed to all traffic from this point onward, as a safety measure. I hauled my heavy camera bag on my shoulder, plus a smaller bag to mask my two cameras and hold some other items I might need: a small bottle of water, my folding back-pillow, wet wipes, cashews. The sun radiated nearly overhead and I joined hundreds of Cubans as we made our way to the Church of San Lazaro some five kilometers ahead. I struggled to breath behind the obligatory face mask – mine was a heavy cloth – and I would have lowered it below my nose but feared sunburn in spite of my sunscreen. Finding little shade en route, I was soon well wetted in my own perspiration.  I paused to extricate my heavy Nikon camera with massive telephoto lens whenever I saw an interesting face or scene.

I paused to extricate my heavy Nikon camera with massive telephoto lens whenever I saw an interesting face or scene.

The Cubans on the road ranged from very devout and dressed in purple or sack-cloth, to the mildly curious and in ordinary clothes. As I approximated the church, periodically I would pass some Cuban who was crawling or dragging himself or herself along on the pavement. These were the penitent and atoning ones, who believed they would release themselves from some suffering, guilt, or need by showing their devotion through physical self-torture. (I had seen exactly the same type of penitents when I was in a town in Paraguay in 2019, but there the number seemed greater. I was later told that many in the area prefer to come in the evening or at night.) I had somewhat of a pain in my lower back from walking with my camera gear in the 95-degree heat, but it was impossible to imagine what the penitents on the ground were going through. At one point, some cool rain briefly fell the road, providing relief to all.

When I entered the front gate, after an hour-and-a-half of walking, I found the church had a relatively modern façade. It was named after someone who had something or another, later deemed to be a miracle by the Catholic Church. A live band was set up in front of the church, and two modern digital projection signs provided a description of events of the day. Periodically penitents arrived to drag themselves to the church, but I noticed some had simply started their crawl at the church’s front gate. Beggars and hawkers had arrayed themselves around the area and there was a heavy police presence in the carnival-like scene. Loose Cuban change (now practically valueless from recent inflation) and even some U.S. pennies littered the pavement, apparently another custom said to yield prosperity. I was later able to squeeze off a few weakly composed “Human Pulse” images, but mainly used my telephoto to document the impactful faces of participants and visitors. Many in the crowd seemed overcome by emotions as they prayed or meditated.

When I entered the front gate, after an hour-and-a-half of walking, I found the church had a relatively modern façade. It was named after someone who had something or another, later deemed to be a miracle by the Catholic Church. A live band was set up in front of the church, and two modern digital projection signs provided a description of events of the day. Periodically penitents arrived to drag themselves to the church, but I noticed some had simply started their crawl at the church’s front gate. Beggars and hawkers had arrayed themselves around the area and there was a heavy police presence in the carnival-like scene. Loose Cuban change (now practically valueless from recent inflation) and even some U.S. pennies littered the pavement, apparently another custom said to yield prosperity. I was later able to squeeze off a few weakly composed “Human Pulse” images, but mainly used my telephoto to document the impactful faces of participants and visitors. Many in the crowd seemed overcome by emotions as they prayed or meditated.

Soon, various church pastors led the crowd in traditional prayers, and many lit purple candles, melting these to the pavement in front of the church. What with the blazing sun, one’s shoes were soon coated on the bottom with a slippery wax; the knees of my pants were dark from my frequent kneeling – not to pray but to take photos. Syncretism was evident in the costumes and some attendees had arranged a large piece of cloth on the ground to hold various objects of spiritual significance, contents manifesting roots in African animism, Caribbean Santaría, and Catholicism. A young girl of about the same age as my little D noticed I was pointing my telephoto lens at her and coyly played hide-and-seek from me until I secured a shot I sought. I had given away the last of my chewing gum shortly ago, so I handed her some paper currency to give to her nearby parents, who had set up a begging bowl.

For some reason beyond me at the time, many attendees had also brought one or more of their dogs, seeking healing from some ailment. It certainly seems contrary to purported compassion to subject animals to intense heat. I later found out that the traditional image in statues and paintings of San Lazarus shows him accompanied by dogs as he walks on crutches. I asked one young woman shrouded in a white head covering about her dog panting in the blazing sun and she said the dog had been sick, but was now miraculously cured. Praise be to Saint Lazarus!

I had envisioned the event to be the capstone to my Cuba trip, but I found the experience somewhat anticlimactic. Too much modern technology, with the live band, the canned music, the JumboTron sign, the pavement (I had long imagined coarse soil or rough earth en route.)

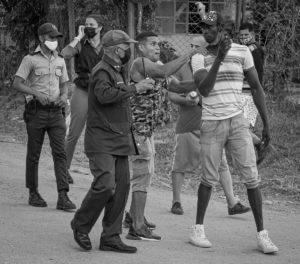

Soon, it was time to start the long walk back, so I could arrive on time for my pickup. The sun still radiated upon all and it took a lot longer for me, as my pace had slowed and my back pain from carrying my equipment had sharpened. I paused to take more photos, buy a soda, take a break inside a defunct train station,  and to buy some farm-grown lettuce to give to Doña Mare. I passed and briefly photographed a street melee involving a tall and strapping young man and some plain-clothed and uniformed police, who were unsuccessful in bringing him down or arresting him.

and to buy some farm-grown lettuce to give to Doña Mare. I passed and briefly photographed a street melee involving a tall and strapping young man and some plain-clothed and uniformed police, who were unsuccessful in bringing him down or arresting him.

Rain returned as a much-needed relief, but I was too hot to contemplate pulling out my poncho. The setting sun birthed a perfect, full moon, which was framed by towering palm trees – I captured this as well. As dusk arrived, so too did I, at the appointed time, and I was transported back to my casa, sore and quite drained of energy. After showering, I ate just a cookie and some cashews, drank some tea, and conked out in my bed. Mocho did not bark that night.

0 Comments