I left the casa early in the morning so I could go to a nearby clinic and take a COVID-19 (PCR) test, required for boarding the plane back to the USA two days later for my return. The morning was to be full of surprises of all sorts.

I was able to hail a taxi and went through what has become a typical dialog with the driver, especially while at the end of my time in Cuba, where I am rapidly depleting my cash funds:

“How much will you charge to go the Clinica Cienfuegos close to here?”

“Twenty U.S. dollars,” he quickly replied, seizing up the archetypal Gringo before him.

“What? It typically costs me just 400 or 500 Cuban pesos (about $5)”

“Ok, that’s fine. Get in; 400 pesos then.”

I paid him 600 pesos.

I could quickly see situation at the clinic was a mess, with dozens of people clustered across the street. I went up to the entrance and asked a uniformed woman defending the door what was going on. She wearily informed me I would have to go across the street and wait “in line,” on the cola. I commented to her that I could see there were so many people and it would take a long time. “Perhaps you need more staff here,” I tactlessly blurted out. She looked at me as if I were radioactive.  The process in such cola situations is, as one approaches a cluster of folk, to ask, “Who is the last one in line?” and memorize not only the physical appearance of that person, but the person in front of them, in case someone leaves. It’s like many things in Cuba today, very Kafkaesque. I realized then there were two clusters – one for the 24-hour COVID-19 PCR test and another for an immediate AntiGen test. But people seemed to move arbitrarily from one cluster to the other, and soon I could no longer tell behind who I was.

The process in such cola situations is, as one approaches a cluster of folk, to ask, “Who is the last one in line?” and memorize not only the physical appearance of that person, but the person in front of them, in case someone leaves. It’s like many things in Cuba today, very Kafkaesque. I realized then there were two clusters – one for the 24-hour COVID-19 PCR test and another for an immediate AntiGen test. But people seemed to move arbitrarily from one cluster to the other, and soon I could no longer tell behind who I was.

Seeking refuge under a tree from the increasing heat of the day, I asked a few people in the PCR cluster how long they had been waiting, and was dismayed to find out that some of them had arrived at 5:00 a.m. and were still waiting in line! I cooled my heels for some 30 minutes to assess the situation, chatting with my miserable but extraordinarily patient comrades, but as it seemed no one was being processed, I finally went up to two more of the staff milling around near the clinic entrance and vented my concerns. “I found that some people have been standing in line for hours. Why are things taking so long?”

(Man) “It’s the payment system.”

“Payment system, you mean computer system? Well, can you not process the tests using paper in a traditional method?”

(Woman) “When are you traveling, Señor? Why don’t you plan to return back here at 4:00 p.m.?”

“I don’t understand, because it should take just about ten minutes to process each test.”

“There’s a lot to do: one has to enter the person in the system, the on-line payment…”

“So, you haven’t resolved this?”

“It’s unresolved.”

“But [this will negatively impact] tourism. There is just too much of a trámite [procedure].”

“Where are you from?”

“The USA.” The woman seemed surprised. “This is absurd,” I continued. Is this situation normal?”

“With the recent reopening of tourism, there have been more in line.”

“Are you one of the nurses?”

“No, I am director of Public Relations.”

“Oh! How funny!” My laughter was followed by hers. “Well, it all makes me sad, in truth, because [Cuba is] losing tourism revenue, owing to trámites like this. Tourists just won’t put up with this.”

“Exactly. We have to find another solution. The truth is, I agree with you,” she added in a hushed tone.

Just to continue on my quixotic path, I said, “I’m going to write some ministers when I return, to ask what one can do to improve this process. Thank you so much – what’s your name?”

“Cristina.”

I thanked Cristina for her frank responses and decided to cut my losses and not spend my entire morning standing around in the heat. While waiting in line I had learned that one could get a rapid AntiGen test at the Havana airport, and decided to opt for that. I walked away and soon made a pleasant discovery of an ice cream shop – with no waiting line – some blocks away (a donut!), then walking another five blocks toward the Malecón promenade.

At that point, I realized I was close to one of Havana’s most well-known attractions, el Hotél Nacional de Cuba. I was able to brazenly walk in and feast my eyes on views of the luxurious locale, walking down to the restaurant, cafeteria, and then outside to the pool area and oasis-like garden overlooking the Caribbean Sea. I ordered a pizza (surprisingly tasty but undercooked) and a drink here. (When paying for the pizza, I realized I had almost no more Cuban pesos, so I asked the cashier if I could pay in Euros. She quickly calculated the exchange, at about 25 pesos to the Euro. I demurred, saying I could get 85 pesos elsewhere. Seeming to mull it over for a minute, she then proposed to exchange at a rate of 80 pesos, and paid this out of her own pocket book.)

After lounging for about an hour out on the expansive patio, surrounded by wealthy international patrons, I became frustrated that I was unable to get any wi-fi signal. I walked out the hotel with three slices left of my pizza in a take-out box, which I soon gave to an apparently homeless and impoverished man. I marveled at the juxtaposition of disparate individuals I had encountered that morning. Near the hotel, I was startled to see a mature tree blocking a well-trod sidewalk. I immediately recognized it as an apt metaphor for Cuba, something like this:

Life in Cuba, a metaphor

My next destination was to a shop in the Habana Vieja district which was said to sell pet supply items. I had to take a taxi and the driver soon confided in me that he was former military intelligence officer. “I know about every U.S. military base,” he claimed, and recited the names of some. “But if anyone ever found out I was telling you this, I could go to jail!” I promised to keep his secret and told him I also used to be in military intelligence as well, with the U.S. Army. With that quick bond of friendship, we arrived, was let out at the entrance to the area, which I had visited some days before to attend a photo exposition.

I was frustrated at my attempts to locate the store and had almost given up for the time being, until I noticed a young woman walking a small Pekinese dog on a leash. I ran up to her and explained my need. Although initially and understandably suspicious of my true intentions, she became quite gracious and offered to escort me some five blocks away. She pointed to a small kiosk in a village park I had not yet visited, where dog harnesses and collars were being sold. I was thrilled by the find and impending closure, and planned to pack up the items and have them delivered to Doña Mare for Mocho, the sad little dog.

I was frustrated at my attempts to locate the store and had almost given up for the time being, until I noticed a young woman walking a small Pekinese dog on a leash. I ran up to her and explained my need. Although initially and understandably suspicious of my true intentions, she became quite gracious and offered to escort me some five blocks away. She pointed to a small kiosk in a village park I had not yet visited, where dog harnesses and collars were being sold. I was thrilled by the find and impending closure, and planned to pack up the items and have them delivered to Doña Mare for Mocho, the sad little dog.

To seal the deal, I also packed up in a canvas bag some remaining items I knew the woman would appreciate, including a bottle of aspirin, my five remaining tea bags, an airline travel kit, and a set of earphones for her son. I included a note to the woman which began, “It is my deepest hope…” I wrote that Mocho had growled at me when I said goodbye to him because, “He was angry that my promise to liberate him did not happen.”

The next day, Humberto picked up the bag and I intend to follow up on the Mocho situation in coming months, via emails to the women owning the Havana casa particular. The following day was overcast and eventually Havana experienced a surprisingly strong storm and deluge. I had scurried to the wi-fi park some 12 blocks away just in time, and was able to hide under the awning of the Hotel Dauville across the street, where I opened my laptop and began to work. As the storm intensified, some dozen other Habaneiros joined me in the sheltered area. A woman shivered from the force of the damp wind. “¡Ay, que frio!” she exclaimed. We refugees began to chat, and I replied in honesty about my country of origin, which raised a few eyebrows.

I used the opportunity to find out more of daily life from those who were on the front lines. One subject I wanted to raise was to confirm what I had learned earlier in the day about milk from the cook at my Havana casa, that there was no fresh milk to be had anywhere. One young woman remarked that such an item was unheard of in these times; there was only powdered milk to be had by most in Cuba – even mothers with children, and strictly limited by the ration book. Since she seemed about university age, I thought to offer her a copy of The New Yorker I had in my bag and she told me she had never learned English – it was just not a subject ever taught in her schools. A man who spoke English quite well but yet who had never traveled abroad mourned the loss of his import business, thriving until the twin daggers of Trump’s additional sanctions and then the pandemic changed everything. I gave him the magazine and he began thumbing through it.

I used the opportunity to find out more of daily life from those who were on the front lines. One subject I wanted to raise was to confirm what I had learned earlier in the day about milk from the cook at my Havana casa, that there was no fresh milk to be had anywhere. One young woman remarked that such an item was unheard of in these times; there was only powdered milk to be had by most in Cuba – even mothers with children, and strictly limited by the ration book. Since she seemed about university age, I thought to offer her a copy of The New Yorker I had in my bag and she told me she had never learned English – it was just not a subject ever taught in her schools. A man who spoke English quite well but yet who had never traveled abroad mourned the loss of his import business, thriving until the twin daggers of Trump’s additional sanctions and then the pandemic changed everything. I gave him the magazine and he began thumbing through it.

My heart goes out to these Cubans, long suffering and with no end in sight to their myriad challenges. For more than 63 years now, they have been in the grip of a proximate and merciless colossus whose hand clenches ever tighter. By what right does my nation perpetrate such an evil? Is the vengeance of those who were forced to relinquish their elite status upon Fidel Castro’s ascension so influential that my nation continues to accept the charting a misguided course through sanctions, embargos, and the consequent blockade? A course that, I should add, has always been counter-productive: it seems only to have more firmly cemented the rigid role of Communist rule on the island nation and impinged upon most freedoms for the Cuban citizens. In spite of many Cuban’s recent venting of frustrations and demonstrations for “Liberty,” she will hold fast to the motto “Pátria o Muerte” in the face of an oppressive bully; standing down is just not in the blood of most endangered peoples. I sat next these people and, for a moment, shared not only their refuge, but their pain; my tears would come later. Here I was, as an ambassador of their foe, yet none of them showed even the slightest hint of recrimination. Fidel’s guidance to the people he led has apparently resonated with each generation:

“𝑊𝑒 ℎ𝑎𝑣𝑒 𝑛𝑜𝑡ℎ𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑎𝑔𝑎𝑖𝑛𝑠𝑡 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝐴𝑚𝑒𝑟𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑛 𝑝𝑒𝑜𝑝𝑙𝑒. 𝑂𝑛 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑎𝑟𝑦; 𝑤𝑒 ℎ𝑎𝑣𝑒 𝑎𝑙𝑤𝑎𝑦𝑠 𝑠𝑝𝑜𝑘𝑒𝑛 𝑣𝑒𝑟𝑦 𝑤𝑒𝑙𝑙 𝑜𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝐴𝑚𝑒𝑟𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑛 𝑝𝑒𝑜𝑝𝑙𝑒. 𝑊𝑒 ℎ𝑎𝑣𝑒 𝑛𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑟 𝑏𝑙𝑎𝑚𝑒𝑑 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝐴𝑚𝑒𝑟𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑛 𝑝𝑒𝑜𝑝𝑙𝑒 𝑓𝑜𝑟 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑒𝑚𝑏𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑜. 𝑊𝑒 ℎ𝑎𝑣𝑒 𝑎𝑙𝑤𝑎𝑦𝑠 𝑏𝑙𝑎𝑚𝑒𝑑 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑔𝑜𝑣𝑒𝑟𝑛𝑚𝑒𝑛𝑡, 𝑎𝑙𝑤𝑎𝑦𝑠. 𝑊𝑒 ℎ𝑎𝑣𝑒 𝑎𝑙𝑤𝑎𝑦𝑠 𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑒𝑑 𝑡𝑜 𝑒𝑑𝑢𝑐𝑎𝑡𝑒 𝑜𝑢𝑟 𝑝𝑒𝑜𝑝𝑙𝑒 𝑤𝑖𝑡ℎ 𝑓𝑒𝑒𝑙𝑖𝑛𝑔𝑠 𝑜𝑓 𝑓𝑟𝑖𝑒𝑛𝑑𝑠ℎ𝑖𝑝 𝑡𝑜𝑤𝑎𝑟𝑑𝑠 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝐴𝑚𝑒𝑟𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑛 𝑝𝑒𝑜𝑝𝑙𝑒.”*

After an hour, the rain abated to a drizzle and I bid adios to my new friends, wishing them well, and walked around the area under a plastic poncho. I began to wonder if this day might be the first one in all my days in Cuba when I would not be able to make photos. But around 4:00, I noticed the clouds parted, and I was able to compose a number of important images. When I returned to the casa particular, I found the electricity to the neighborhood had been cut for some hours, owing to the intense storm; it would not return until early the next morning.

-

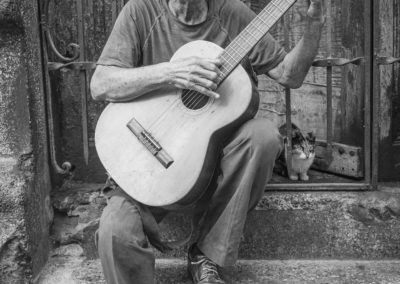

I had a nice conversation with Thomas, an elder musician, who was sitting in front of his house with his calico cat. Belascoain, La Habana centro.

-

Juxtaposition of classic and modern signage, Havana Centro.

-

"Habaneiros" – Cuban residents of Havana, play dominoes in the Habana Centro neighborhood of the capital. © 2022 John D. Elliott • www.TheHumanPulse.com

-

A porter drags his load on a squeaky dolly in Havana's deteriorated central district. Cubans continue to struggle under adverse economic conditions, as evidenced by this scene in the Habana Centro district of the capital. © 2022 John D. Elliott • www.TheHumanPulse.com

* Castro Speech to Pastors for Peace, December 1, 1992 (http://lanic.utexas.edu/project/castro/db/1992/19921129-1.html)

0 Comments