Chapter V. The Angel and The General

On October 18, my birthday, I started the day with a familiar, empty feeling. I had little reason to celebrate, and deferred mentioning the occasion to Mustafa* at breakfast. I again scoured the Internet for any news on Viva Palestina, and read a paragraph of despair from their official Web site: the convoy had been again delayed from boarding the ship, owing to some Egyptian government demands for additional assurances to the ship’s owners and captain. I tuned the hotel reception lobby television to the Aljezeera News, which broadcasts in Arabic. After a while I realized they had no report on the convoy, but I was able to get confirmation in English from Press TV, the Iranian satellite channel, that the flotilla was still in Syria. The situation with the convoy was bad news for Fatima, the German Muslim woman, since she had just one more day to wait until she must return to Caior to catch her flight. But it was hopeful news for me, since it gave me time to get back to Al Arish.

I departed Cairo in the afternoon, taking the same circuitous series of transport modes. Laden with two large bags and two smaller ones–more than a hundred pounds on my back and shoulders–I walked the four blocks to the nearest Metro station, at Tahir Square. Alone this time, I then tried to figure out which train would take me to the last Cairo stop on the northern route; I had to take a second train from that stop.

I departed Cairo in the afternoon, taking the same circuitous series of transport modes. Laden with two large bags and two smaller ones–more than a hundred pounds on my back and shoulders–I walked the four blocks to the nearest Metro station, at Tahir Square. Alone this time, I then tried to figure out which train would take me to the last Cairo stop on the northern route; I had to take a second train from that stop.

Deboarding, I walked out of station and through the crowded and filthy market stalls, to a sort of bus depot located underneath an expressway. After purchasing my bus ticket in Arabic (in a failed attempt to avoid the surcharge foreigners must often pay in this country price), I fed some stray cats while I waited for the bus to arrive. Once on board the 5:00 p.m. bus, I found my seat by associating the Arabic numerals scrawled on my flimsy ticket with the painted ones over the seats. The initial trip I had made on this route was in daylight, and I recalled how I had been terribly excited when I first saw the renowned Suez Canal, which I had first learned about as a child. Crossing it on a modern bridge, looking down upon the huge ships making their way on the vital waterway, and watching the endless expanse of desert fly by had made the initial trip go quickly. But this time, my view out of the window was greeted by darkness, or an occasional, dimly lit police checkpoint, and these failed to raise my spirits.

When I arrived in Al Arish, it was late at night. The bus deboarded at a different location than the one from which I had departed, and I was disoriented. A verbal and subsequent fist fight then took place between two of the male passengers outside of the bus, and I watched for a minute as the confrontation escalated, and then, just as quickly, subsided. A couple of pirate taxi drivers tried to claim me for their fare, but I sought a legitimate taxi, which I could identify by the color of their vehicles; they had meters to ensure accuracy. My driver seemed to be a very pious man, judging from the Islamic prayer songs emanating from his radio. After I told him the name of a hotel which had been highly recommended to me by Fatima when I had last seen her, I settled in for the ride and tried to make sense of the music. The songs were repetitions of various suras from the Qur’an, and the tones seemed random and annoying, almost a drone. I wondered what would happen if some female vocalist would dare to come out with sura vocals. While this was at least culturally forbidden, perhaps it would be more pleasurable to listen to! Just when I thought the song was over, the chanting Muezzin would start yet another verse, and the monotony would continue. I resolved to try to listen to this type of singing some more, as a few years ago I had a similar negative impression of hip-hop music, yet after some searching had found a few artists of this genre I would come to appreciate.

I was startled when the taxi pulled up to the very same hotel I had left three days earlier. I guess I hadn’t recognized its name when Fatima had recommended it, or perhaps I couldn’t understand her pronunciation. Suddenly realizing I was now a petty thief in a foreign land, I wondered if the cheap metal ashtray I had borrowed for use in providing water to the donkeys at the crossing might have been connected to me, and planned to return it now that I had a chance. But no one at the front desk asked me about it or seemed bothered by my reappearance, and in fact the young chaps during the check-in process appeared quite pleased to see me again. The room I secured was a few notches lower in quality than the one Nayal and Sakher† shared with me, but I was happy to at least have a real toilet. It would run me 80 ginea per night–about $14, and half what I was paying in Cairo for a much worse lodging. I asked the hotel bellhop who showed me my room where I might get some soup or dinner and when he said every restaurant was pretty much closed, I realized how late it was. I satisfied myself with some of the raw almonds I had bought a few days earlier at the Rafah border and a fresh apple, washed down with bottled water. I wanted to turn on Aljazeera’s news channel, but found the television did not work, and I had to change rooms to get a working set. The news did not report anything on the Viva Palestina crossing, however, and I turned in for the night. I realized my birthday had come and gone.

When I had left Sakher in Al Arish, he said he was going to go back to the Rafah crossing and keep trying to get in to Gaza, at least one more day. After all, he said, Col. Walid had told him his “papers were almost approved”. The next morning I called Sakher from the hotel to see what had happened. I couldn’t reach him and wondered if he had given up and returned to Dubai. Sakher’s story was different than Nayal’s, in that the former had family members that were not allowed to leave Gaza for lack of proper papers. I next wrote some E-mail letters to a member of the Viva Palestina team, whose blog I had been following, and sought some connections to the headquarters staff as well. Although I had written these people some three days earlier, I had not received any reply. I was unable to get much information and the Viva Palestina Web site always reported news in a most optimistic tone, and was a couple days behind in updates as well. I had to use my intuition, which told me that the ships carrying the convoy would leave that day or perhaps the next.

I ate a small breakfast of fuul, the popular Egyptian dish of cold beans with olive oil and herbs, in the hotel dining hall. Returning to my room, I packed a few essentials into my back pack day bag: a couple of apples, a large bag of local raw almonds I had bought at the border a few days earlier, small bottle of water, earplugs (for the blasted and incessant car honking), compass (I didn’t want to end up walking in the wrong direction here, as I had done the week before when exploring Cairo), half-roll of toilet paper, sun screen, pens, aspirin, LED flashlight, chewing gum, eye drops, two cell phones, three rolls of 220 film, and a light meter. I also brought my two cameras (my new Nikon D-80 digital and the film camera, a Mamiya 645 medium-format monster which weighed as much as everything else combined).

Al Arish reminded me of a sort of distant outpost in the American Wild West. It was dusty, and sand from the nearby sea shore permeated everywhere, often piled a inches thick along some areas in the street. It seemed to have recovered from the episode in early 2008, when the inhabitants of the Gaza Strip had used explosives and bulldozers to break down the walls holding them. Tens of thousands of Gazans had poured across the border into Egypt, to buy needed supplies and commodities. But the brief respite was generally more inconvenience than it was worth, as the Egyptian authorities forced the shop owners of Al Arish to close, and blocked the major roads. Many Gazans spent days trying to go around the road blocks, but most returned to Palestine empty-handed. Today, however, Al Arish shops seemed to me to be full of every necessary supply–even luxury items, such as lingerie and rich chocolates. The charm of an ancient town was merged here with the bustle of a smaller version Cairo, but conditions were often primitive once one left the center of town.

I walked down a few streets, initially searching for a T-shirt that promoted Palestine, but not having any success with that, I soon came across an alleyway food market. I immediately realized that here would be an ideal location to linger for a while, to take some photos for my ongoing series, “The Human Pulse”. Practically a lifelong photographer, I had been working on this series for more than 30 years, finding interesting places to document the myriad activities of humankind. I had had many exhibitions of my photos in the past five years, and the series grew a bit every time I traveled. I saw an intersection of two alleys in the middle of the marketplace, and was blessed (as I often have been) to find a couple of steps upon which to stand, to secure my preferred higher vantage point. I pulled out my Mamiya camera from my day pack and prepared it with some slow but sharp film, then took a meter reading with the handheld device: f5.6 at 60th of a second for the angles which showed the sunlight, and a bit slower for those scenes which had more shade. By now, people were pausing in their shopping or selling, to stare at me. But I knew from hundreds of situations like this that if I wait long enough and appear benign, people will eventually find me virtually invisible and go back to their normal activities. What I sought was the combination of activity and motion, with the character of culture, and under the most ideal lighting conditions. “The Human Pulse,” is choreographing a dance by pure intention. I previsualize the scene and wait for everything to come together: the people selling yams on the left must not have their back to me too much; the teens on the right should be playfully tossing a green pepper to each other; the little kids in center should be running or playing; perhaps a greeting hug in the distance. I choose to shoot from a higher angle, about three to five feet more than the plane of action, so that there is more separation of the “actors,” and also because it gives a sort of angel-like, hovering sensation which I have adored since I saw the German film “Wings of Desire” years ago.

I stood in my preferred position and kept the Mamiya near my eye, surveying the scene. Waiting. Occasionally things would look like they were “taking shape” and I would position my right index finger over the softly rounded shutter release button. If it looked as if there might be a good opportunity, I would take just one photo, perhaps every five to ten minutes. The camera complains loudly, as the mirror is quite large and must get out of the way before the curtains of the shutter open. Then there is a second-long sound as the film automatically advances and the shutter is cocked to prepare for the next opportunity. I imagine many precision gear teeth meshing. If anyone is nearby, they may look up to ascertain what kind of animal I am holding, so curious is the sound. I always find it rather pleasurable, as machine sounds go.

I stood in the same position for a good hour, sometimes having to move a few inches–either to get the best angle, or if someone needed to pass around me. A fellow was selling cheese from a stand just behind me. The vendors nearby feigned concern at first, some wanting to know what I was doing there. When I would engage with them in some Arabic, smile, and show I was harmless, they became good natured. The boys in the area, some of whom were working as vegetable vendors and some who just passed by, were the most playful. At first a few of them demanded I take a photo of just them. For this I would pull out my tiny, digital Canon camera, which is easy to use and gives immediate gratification on a screen on the back of the unit. Then I would return to my position, continue observing, and wait. And wait. I began to see just the scene I hoped for, and this happened when some children came into the picture, with a bicycle or in pairs, interacting with each other. On the other side, a young man tossed a green pepper to another and for a few seconds a play-fight ensued. A couple of women of indeterminate age, in their ominous niqab black robes paused at the fruit area. The only visible part of the women were their eyes, darting here and there as they conversed with hidden lips.

I heard the braying of a donkey, which piqued my curiosity. Was the animal in distress? Was it sad or lonely or exhausted? I hopped down from the steps and walked down the street toward where I had heard the sound. I discovered a small, grey donkey with its head lowered, attached to an old, wooden cart, devoid of cargo. I remembered I had stashed three pieces of ayish, the typical Egyptian round bread, from the hotel breakfast and removed the day bag from my shoulders to locate the food. The donkey sniffed tentatively at the bread, and, finding it attractive, took it from my outreached hand, its lips briefly touching me. I talked softly to the animal, rewarding it with energy not just from my hand but from my heart. I assumed its lot in life was terrible, working all the days and nights as a draft animal, in a part of the world which saw these creatures only as soulless implements of labor.  A couple of teenage boys came by to see what I was doing, so I gave one of them my small, digital camera and asked him to take a snapshot of me with the donkey, for which both the boy and the donkey obliged.

A couple of teenage boys came by to see what I was doing, so I gave one of them my small, digital camera and asked him to take a snapshot of me with the donkey, for which both the boy and the donkey obliged.

When this was done, I thought I would keep walking, to discover some new places to see or photograph. Yet I had a feeling that, instead, I should return to the original place I had been, in the market alley intersection. I thought, “This is not like me. I usually move forward, not go back.” I walked the half-block back to my perch of steps and set up again there, waiting for another scene to emerge.

After about five minutes, I heard a voice ask, “Do you speak English?” I looked to my left and saw a man, with coarse and olive colored skin. He reminded me a bit like the photos in history books of Abraham Lincoln. I said, “Well…I speak English. And Spanish, and French, and even a bit of Russian. I am also learning Arabic.” He seemed dubious and so I said a few things to him in Spanish, a language in which I am fairly fluent. The Spanish he returned was crude, and since his English was fairly good, I continued in this language. I mentioned my Arabic studies in Cairo and informed him that, “I am making photos of the market and the people here.” He heartily replied, “You should see the Bedouin market, then. It’s on Thursday. They sell camels and everything.” I was intrigued and made a mental note to return the next day to do some more photography. I also mentioned, “I’m looking for T-shirts with the Palestinian flag, but I cannot find any.” His eyes lit up and he said he knew where to find shirts, and perhaps even some traditional kaffiyeh scarves with such a flag.

After about five minutes, I heard a voice ask, “Do you speak English?” I looked to my left and saw a man, with coarse and olive colored skin. He reminded me a bit like the photos in history books of Abraham Lincoln. I said, “Well…I speak English. And Spanish, and French, and even a bit of Russian. I am also learning Arabic.” He seemed dubious and so I said a few things to him in Spanish, a language in which I am fairly fluent. The Spanish he returned was crude, and since his English was fairly good, I continued in this language. I mentioned my Arabic studies in Cairo and informed him that, “I am making photos of the market and the people here.” He heartily replied, “You should see the Bedouin market, then. It’s on Thursday. They sell camels and everything.” I was intrigued and made a mental note to return the next day to do some more photography. I also mentioned, “I’m looking for T-shirts with the Palestinian flag, but I cannot find any.” His eyes lit up and he said he knew where to find shirts, and perhaps even some traditional kaffiyeh scarves with such a flag.

Ever since some vexing experiences a few years earlier in Morocco, I have maintained a very strong defense against people in foreign countries volunteering to be my “guide,” especially to shops. But for some reason, I felt very comfortable and trusting of this man. He told me he went by the name Kusai, yet the glossy and unusually wide, folding card which he handed me instead said, “Mohamed Samir, Egypt Tourism, Travel and Aviation Service”. I walked with him for a few blocks, ending up at the same area in which I had sought my T-shirts a few hours earlier. I mentioned I had had no luck with these shops, so we went to another street. Here, he was successful in finding me the kaffiyeh, for just 15 ginea, or about $2.50. I was initially pleased to see it had some Arabic words woven on each end, but when he told me the meaning, my enthusiasm lessened: it said, “Jerusalem for a Palestinian capital,” a proposal I had come to disagree with, as I believe is unnecessarily mixing religion and state, as counter-productive as Israel’s intention is to relocate its capital from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Smiling, he modeled the scarf on both his head and around his neck, to show me the typical style of use.

As we resumed walking, I began mentioning to him my interest in getting across into Palestine’s Gaza Strip. He replied, “I know a woman named Ellen who has been there many, many times, and who lives right here in Al Arish. You can talk with her if you wish. She is a nun and also a vegetarian.” My ears perked higher at this last item, as I had yet to meet a fellow vegetarian in Egypt since I had arrived at the end of the previous month. I told him I would like to meet her, surely. I remembered Basata, the excellent, seaside restaurant I had dined at with Sakher and Nayal the week before, and the delicious tomato soup there, and I suggested that he might call her and ask her to meet us there that afternoon. I then confided in him that I had been very frustrated by all the Egyptian government red tape I had encountered in my attempts to gain permission to cross the Rafah border. He replied, “Well, my good friend Hamdi knows some people in Il Mukhabarat, and he can surely help you to enter”. Again, my interest edged up significantly. Could Kusai be the key to my goal? But the final tidbit Kusai mentioned was the most surprising, for he said, “And I have a friend Greg, who is a US diplomat living here now for 20 years, so surely he can help you.” Kusai then used his cell phone and called Ellen and Hamdi, to invite them to the restaurant at 5:00 p.m. When he called Greg, I requested a moment to speak to him. I mentioned that I was a candidate for the US Foreign Service, and asked him to also join us at Basata. Surprisingly, Greg readily accepted the invitation, even on the short notice of just three hours.

We found no T-shirts with Palestinian flags or support in all of Al Arish. Perhaps the memory of the 2008 invasion from Gaza was too fresh. Kusai invited me to his house for tea. He lived in an apartment on the third floor of a building not far from the town center. His wife, wearing a dark hijab head covering and abeya robe, served us and I chose coffee (American style is simply called by the brand name of Nescafé), with sugar. Kusai then presented me with half a dozen brochures extolling the virtues of Islam and insisted I take them for subsequent reading, which–since I can never learn too much about the ways religions promote themselves, I was pleased to do. From one of the apartment windows, there was a dramatic view of the town, and, in the distance, the Mediterranean Sea. I took some photos, and then asked if I could take the stairs to the roof of his building to take some more. Unbidden, he carried our drinks behind me, on a metal tray. After some time enjoying the view and the warm sun, we descended the stairs and into his place, where we exchanged further pleasantries and light conversation. I began to notice the physical way Egyptian men have in communicating, as Kusai frequently would punctuate his words by amiably poking his index finger into my side or shoulder. After a while, I moved a safer distance from him on the sofa.

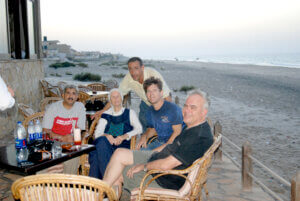

When it was time to depart, we then took a taxi the 5 miles west to the fine restaurant, Basata. Entering, we passing dozens of framed photos of restaurant management posing with various actors and politicians–none of whom I could readily identify–and emerged on the other side of the restaurant, which opened up to the beach and seaside. It was nearing sunset and, while we waited, I took some photos with one of my digital cameras; Kusai came onto the beach with me and posed me with the sun setting at my back. Then Hamdi, Ellen and Greg arrived and we introduced ourselves. Hamdi Mazouz was a stout fellow of perhaps 45 years of age, with graying hair, a lighthearted disposition and a twinkle in his eye. He explained that he ran an English and computer education school and invited me to visit. Ellen Crothers an American of perhaps 70 years of age, of a sweet but intensely inquisitive disposition, and what little of her grey hair that I could see was hidden by a sort of habit, which trailed down on to a smock-like dress, which covered her feet as well. Most of her arms were covered by a white, long-sleeved shirt, and she wore a locally made purse around her neck. Greg Jahnson, also American was perhaps 55, stocky, with hair more salt than pepper, and initially had a taciturn disposition; after a while, it occurred to me that he would speak only when something important came to mind. I tried to contain all my questions to each of these people, and diverged instead to the subject of photography. I showed Greg my book of photography, a copy of which I had in my backpack, and he leafed soberly through the pages, making kind comments here and there. I could tell he was absorbing a lot from each image. (Greg later corrected Kusai’s description of his job, not in diplomacy but rather with USAID, the United States federal government agency primarily responsible for administering civilian foreign aid. He is a contractor managing a program to improve the standard of living for poor, Bedouin communities in Central Sinai.)

As the wind seemed too boisterous to eat on the patio, our group relocated to a table inside the restaurant, and Greg inquired into my organization, AidWEST. I showed my new friends some photos of my Haiti experiences from earlier that year and discussed some of the objectives I saw for the non-governmental organization. Greg wondered aloud about the reasons other than my diplomatic language studies for my being in Egypt and I mentioned that I also hoped to bring some medicines into Gaza. At that point, Hamdi said he would immediately contact a friend of his who was a general with Il Mukhabarat, and that we might even be able to go meet with this official the very next day. I was thrilled. I spoke briefly with Ellen, about her experiences in Gaza and the border area as well. The conversation flowed easily and at the end of the dinner, when I went with the group to the front of the restaurant to pay, Hamdi said he would take care of my portion of the bill and he wouldn’t even allow me to contribute; such was the custom in this part of the world.

As the wind seemed too boisterous to eat on the patio, our group relocated to a table inside the restaurant, and Greg inquired into my organization, AidWEST. I showed my new friends some photos of my Haiti experiences from earlier that year and discussed some of the objectives I saw for the non-governmental organization. Greg wondered aloud about the reasons other than my diplomatic language studies for my being in Egypt and I mentioned that I also hoped to bring some medicines into Gaza. At that point, Hamdi said he would immediately contact a friend of his who was a general with Il Mukhabarat, and that we might even be able to go meet with this official the very next day. I was thrilled. I spoke briefly with Ellen, about her experiences in Gaza and the border area as well. The conversation flowed easily and at the end of the dinner, when I went with the group to the front of the restaurant to pay, Hamdi said he would take care of my portion of the bill and he wouldn’t even allow me to contribute; such was the custom in this part of the world.

Ellen invited us all to her house for tea and coffee, and she, Kusai and I took a taxi there, a few miles further to the West. She lived in a small, rather spartan condominium-style house directly on the beach. Here I also met a friend of hers, Lilia Cameron, a young lady from England who had just arrived to Al Arish a few hours earlier, having been invited by Ellen to stay in one of her vacant rooms while Lilia visited Egypt. Around 28, she was slim and tall, wore no makeup and seemed very serious. Lilia spoke Arabic of the Modern Standard variant and was well traveled throughout the Arab world; she had just come from spending some time in Jordan and Syria and was headed to another Arab country in a few days. A convert to Islam, she wore the abeya and hijab and I asked her some superficial questions, trying to not delve too deeply into some sensitive subjects on my mind about her reasons for converting.

At the end of the delightful evening, I returned to the neighborhood of my hotel in a taxi with Kusai and his wife, who we had picked up en route. It let us out a few streets away, since there was a traffic problem, even at 10 p.m.; Egyptians are well-known to be night owls and many shoppers filled the nighttime streets. What was even more surprising to me was the number of young children out so late. How did the parents ever get up for 4:30 a.m. prayers? When we passed by a bakery, I insisted that we  go inside, so I might buy a slice of cake and a tiny candle. Now I was ready to celebrate my birthday! Meeting Kusai had been a stroke of great fortune, and I told him that he might just be “my angel”. I said good night to him and his wife in front of the hotel and, in the solitude of my Spartan room, lit the candle, made my wish and blew it out with gusto.

go inside, so I might buy a slice of cake and a tiny candle. Now I was ready to celebrate my birthday! Meeting Kusai had been a stroke of great fortune, and I told him that he might just be “my angel”. I said good night to him and his wife in front of the hotel and, in the solitude of my Spartan room, lit the candle, made my wish and blew it out with gusto.

* Mustafa Aram, a retired Libyan foreign minister for The Arab League. He proved to be an excellent resource for the background information and contacts I would need on my supply mission to Gaza.

† Sakher and Nayal were two men with whom I had earlier shared a taxi ride for three hours across the bleak desert and over the Suez Canal bridge, to the city of Port Saïd.

0 Comments