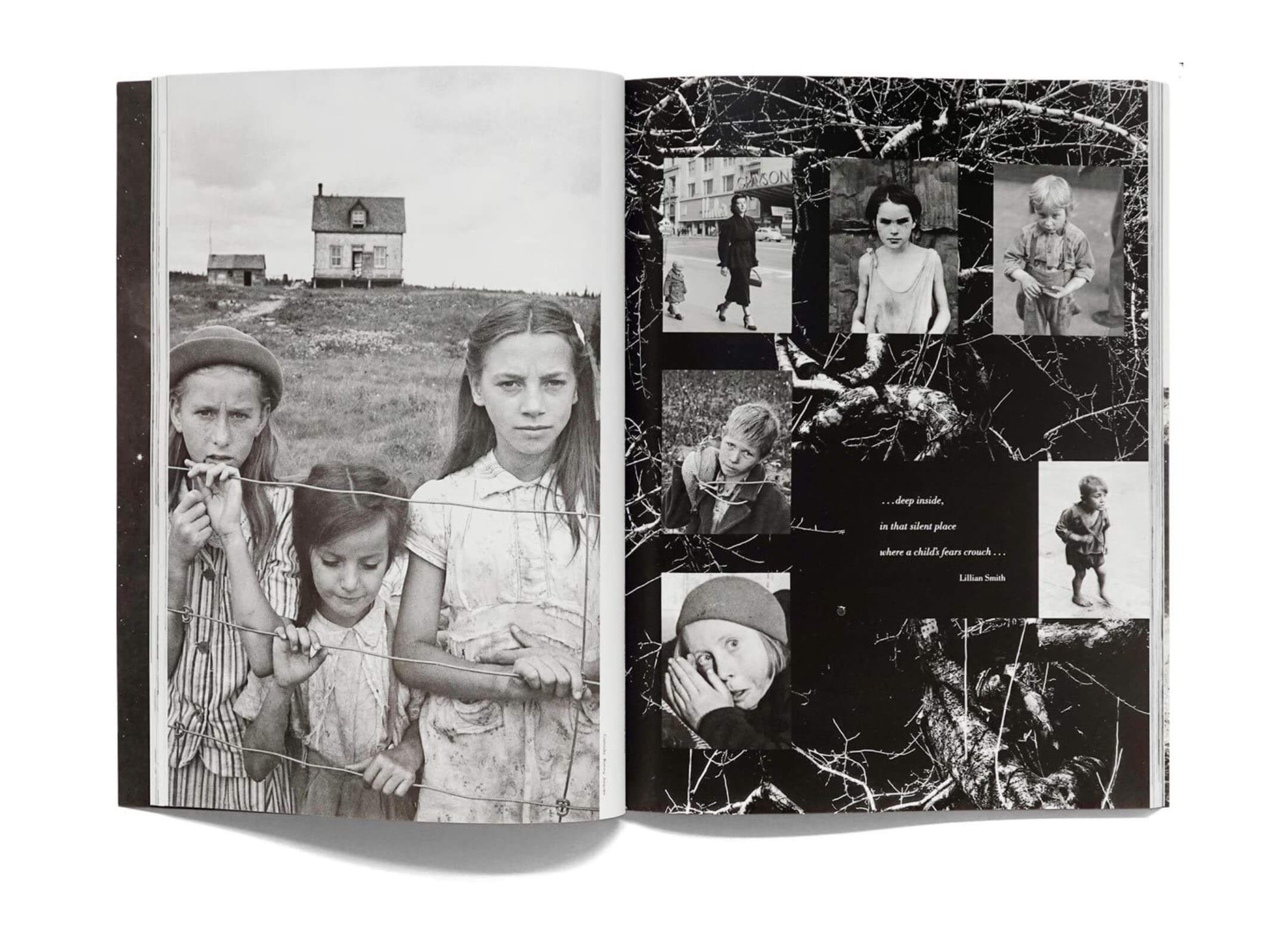

When I was about six, I came across in my father’s library The Family of Man, a book published in 1955 to coincide with a seminal Museum of Modern Art exhibition of photography. Edited by Edward Steichen and incorporating choice selections submitted by thousands of photographers from all over the world, demand has seen the book continuously published since then in more than thirty editions. Only decades later did I recollect perusing it with interest as a child, and the memories of many images remained vivid. Recently musing upon the genesis of my series The Human Pulse, I began to realize how influential this book was on my photographic vision.

When I was about six, I came across in my father’s library The Family of Man, a book published in 1955 to coincide with a seminal Museum of Modern Art exhibition of photography. Edited by Edward Steichen and incorporating choice selections submitted by thousands of photographers from all over the world, demand has seen the book continuously published since then in more than thirty editions. Only decades later did I recollect perusing it with interest as a child, and the memories of many images remained vivid. Recently musing upon the genesis of my series The Human Pulse, I began to realize how influential this book was on my photographic vision.

Some years after my childhood explorations within the pages of The Family of Man, I discovered as a teen the thrill of traveling to and living in other countries, and came to appreciate all the diversity of ideas and approaches of different peoples. Yet, growing up in New York City, disparate cultures had always been enriching my life. My father would delight in taking the family to Chinese or Polish restaurants and during our home dinners he often played records with music from far-flung continents. In spite of my Jewish heritage and Christian mother’s misgivings, he used to teach my two sisters and me the Muslim call to prayer, words of the adhan which remain chiseled in my mind.

The city of my youth was then as it is today blessed with the glittering galaxy of human activity and ethnic variety. One of my earliest memories – probably at around age four – is peering outside our apartment window overlooking the building courtyard. Some Jewish families built over many days temporary sukkah structures from old doors and such, an annual tradition preceding Yom Kippur. From the front side of our building, even in the 1960s, I could sometimes observe from a window the rag collectors and junk dealers in their dilapidated horse-drawn carts, or a scissors-sharpener, loudly promoting his craft up and down our Manhattan street. A visit to other neighborhoods was a montage of diverse faces, scents and sounds, especially when I was brought to the downtown fish market or a Greek shop for feta cheese and olives. My friends in school often hailed from strange places that captured my curiosity, such as a girl from Saudi Arabia in first grade, or buddies born in islands of the Caribbean.

I was thirteen when my sisters and I were suddenly informed by my father that the family would be moving to Florida. I had my reservations, however arriving in the Miami area in the ‘70s was to be a treat. The increasingly dominant culture of the Cuban émigrés piqued my interest, and soon I found myself studying Spanish–if only so I could decipher what some classmates were saying about me.

The next year, I took a class in drafting, part of which involved learning camera and darkroom skills. Smitten, I soon saved up some money from my first job (as a camera store clerk) for an adequate camera: a 35mm Mamiya Sensorex SLR. In high school, I joined the marching band and my mother somehow came up with the money for me to go on a school-led tour to five European countries, and I was quickly bitten by the travel bug.

The next year, I took a class in drafting, part of which involved learning camera and darkroom skills. Smitten, I soon saved up some money from my first job (as a camera store clerk) for an adequate camera: a 35mm Mamiya Sensorex SLR. In high school, I joined the marching band and my mother somehow came up with the money for me to go on a school-led tour to five European countries, and I was quickly bitten by the travel bug.

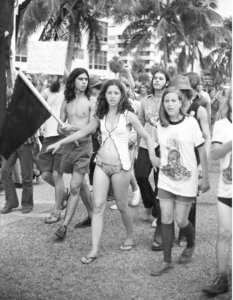

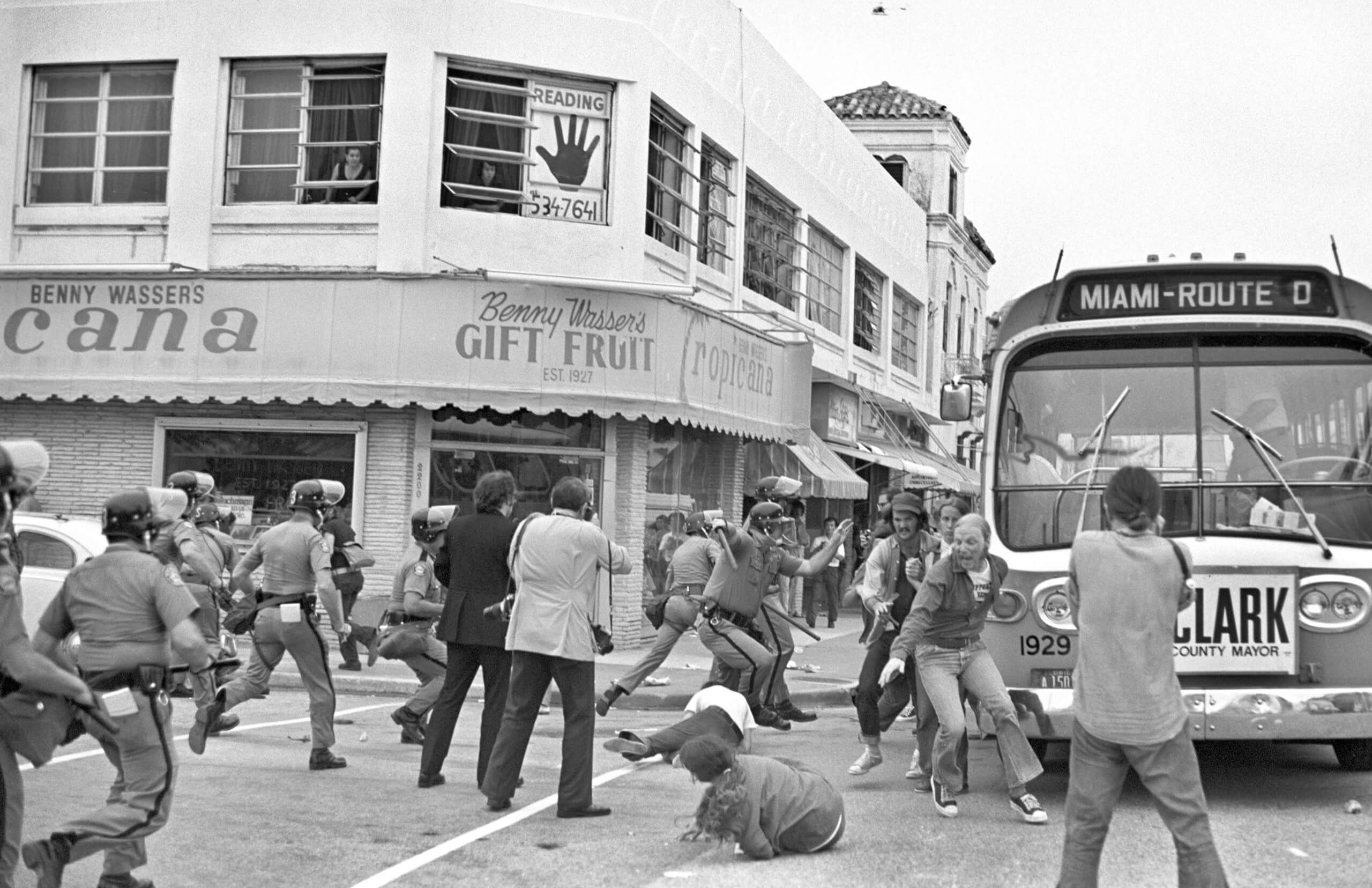

A seminal experience was when the 1972 presidential nominating conventions came to Miami. I somehow convinced my mother to allow me to take the lengthy bus ride to the convention site on many days, where I would prowl both inside and outside the Convention hall, pausing to document the excitement, demonstrations, and violent clashes.* Returning to my small bedroom closet darkroom, I was thrilled to be able to develop film and prints documenting my excursions. (1)

A seminal experience was when the 1972 presidential nominating conventions came to Miami. I somehow convinced my mother to allow me to take the lengthy bus ride to the convention site on many days, where I would prowl both inside and outside the Convention hall, pausing to document the excitement, demonstrations, and violent clashes.* Returning to my small bedroom closet darkroom, I was thrilled to be able to develop film and prints documenting my excursions. (1)

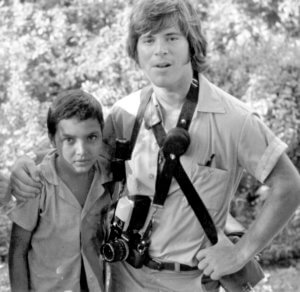

The following year, however, my travels were markedly different in terms of culture and destination. During my first year in high school, I had joined a volunteer health care group, Amigos de Las America, and trained with two-dozen other youths from the area, in medicine, cultural awareness, and Spanish.  That summer, I traveled for nearly a month throughout a small, mountainous region in Nicaragua, giving measles vaccinations to children, polio drops to babies, and English lessons to inhabitants in and near an impoverished town. Using a new (Canon) camera, I began to document the sadness of disease, dirt floors and distended bellies; but also the shy smiles of children and the regular rewards of pink clouds and redolent sunsets at the close of each day. I served again as a volunteer for this program the following year, in a different part of Nicaragua; then in my first summer of college, as part of the program staff, in Honduras for much of the summer break. These three summers became the crucible for my motivation to reach out to the people of the world, not just as a photographer but a humanitarian.

That summer, I traveled for nearly a month throughout a small, mountainous region in Nicaragua, giving measles vaccinations to children, polio drops to babies, and English lessons to inhabitants in and near an impoverished town. Using a new (Canon) camera, I began to document the sadness of disease, dirt floors and distended bellies; but also the shy smiles of children and the regular rewards of pink clouds and redolent sunsets at the close of each day. I served again as a volunteer for this program the following year, in a different part of Nicaragua; then in my first summer of college, as part of the program staff, in Honduras for much of the summer break. These three summers became the crucible for my motivation to reach out to the people of the world, not just as a photographer but a humanitarian.

I chose a college that had a reputable journalism program, Ohio University, but which also had a strong fine arts and photography program. My four years at OU were a blissful immersion into art history and photography technique. I studied and was influenced by many photography role models, from Diane Arbus to Henri Cartier-Bresson. (The former influenced my first photographic series, “Victims,” which echoed her sense of the unusual and mysterious.) Just prior to graduation and the year following, I sought and received photojournalism assignments for a magazine and documented indigenous life in Guatemala and Mexico. Then, in 1983, on a whim, I quit my corporate job and traveled throughout European and North African countries surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. It was on this two-month creative and spiritual sojourn that I took the series’ first photo: “Reservoir Boys, Meknes, Morocco”.

Marriage and starting a family paused the world travels somewhat for a decade, except for a lengthy and high-yielding trip to India with the Rotary Foundation. But as my first daughter Danielle entered her teenage years, I resolved to show her the world, and my excursions resumed with two backpacking trips we made to England and France. Professionally, my career often employed my photography, but more as a commercial craft. While working at a corporate audio-visual job, I joined the U.S. Army Reserves. I served as a military photographer for four years, then spent a decade in corporate communications, followed by 18 years as creative director for my own ad agency.

An unanticipated career with the U.S. Foreign Service began in 2011. I received hugely rewarding opportunities to engage in two lengthy overseas assignments, first in Brazil and then in Saudi Arabia. While in these visually rich lands and nearby nations, during off hours I indulged in unhurried photographic explorations. Even after my 11-year career as a diplomat have now come to a close, I ever yearn to reach out to more foreign hands, learn new languages, and discover new friends at different destinations.

From the elderly villagers in China, to the Icelandic natives bathing in their thermal springs, to the Tamils in India who taught me how to avoid marauding elephants, I have found the keys to friendship are as simple as saying “thank you” in the indigenous lingo, a willingness to receive a cup of tea or a typical bread, and offering smiles seasoned with humility. When I’m lucky, in addition to sharing such friendship and adventure, I return with exposed film or brimming camera cards, nascent witnesses to my creative vision.

• • •

As with The Family of Man, I strive to paint a multi-faceted spectrum of global humanity – joy to suffering, spontaneity to reflection. The influential memories of the book’s photographs were but a starting point for my series. Shortly before my 1983 Mediterranean trip, I came across a photo looking down upon a city street. Captivated by the dreamlike timelessness of interacting human shapes, I sought higher vantage points when previsualizing many of my photos. I was likewise impacted by Wim Wenders’ lovely film, Wings of Desire, an existentialist story of two German angels who observe and influence quotidian life from various overhead perches; I resolved to incorporate the film’s mood in some of my photos. As I am a long-time human rights activist, the social documentary aspect of the series is intentional. All titles are deliberately undated, to blur the zeitgeist. And to elicit curiosity, I am often drawn to ambiguity of event or action, for I believe questions are often more enlightening than answers.

(1) “Miami Bus Riot,” is one of the photos I took during the 1972 Miami conventions, from my 15-year-old perspective. I discovered to my delight that there was much information to later perceive –– such as the woman in the fortune-teller’s window.

[This article is adapted from my book, “The Human Pulse”.]

0 Comments