– a final spectacle in the waning days of hippydom –

The national media was buzzing and the nectar that summer of 1972 was a double dose of news practically in my back yard: the Democratic and Republican conventions in Miami Beach. Everyone in Florida seemed either excited or apprehensive about the focus to the south, just a couple of bus rides from the Coral Gables home where I lived with my parents and two sisters. I had just become interested in photography earlier that year, and the important events seemed to me to be the perfect forge for my imperfect skills. From occasional film clips on the local news, everyone was reminded that four years earlier, the previous national conventions in Chicago triggered national outrage at the oppressive brutality of police countering anti-Vietnam War demonstrations. So I suspected there would be many interesting scenes to capture on film.

My first camera, a Miranda Sensorex 35mm, was a far cry from a pro’s Nikon or Leica; I had just one lens, the 50mm normal. I had forsaken purchasing any additional equipment so I could invest in a decent darkroom enlarger, which I set up in my bedroom closet. Now I felt I could do it all, but my actual photography experience was minimal, consisting of exposing a few rolls with images of pets and school friends.

My first camera, a Miranda Sensorex 35mm, was a far cry from a pro’s Nikon or Leica; I had just one lens, the 50mm normal. I had forsaken purchasing any additional equipment so I could invest in a decent darkroom enlarger, which I set up in my bedroom closet. Now I felt I could do it all, but my actual photography experience was minimal, consisting of exposing a few rolls with images of pets and school friends.

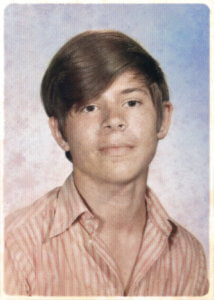

It had been just a few months since I had learned the science and a little more about the art of photography–as part of an architecture/drafting class in junior high school. But as a child, I had absorbed and enjoyed the photography of Life Magazine. I particularly appreciated a Life book we owned, The Family of Man, with its vibrant and emotional studies of people from around the world.

So, In spite of the numerous misgivings of my mother, I would set off one sun-baked morning with camera bag and just 5 rolls of black-and-white film and soon found myself deboarding my final bus and walking toward the Miami Beach Convention Center. It was my trial by fire and would be the first of two sojourns to a spectacle which would form a foundation for my romance with photography as a creative outlet and communications tool. The vibrancy of the anti-Vietnam War movement, in all its confrontational colors, would reach its climax that summer. Nixon’s “peace with honor” plan (promoted by his administration as “Vietnamization”) had already failed, and the daily toll of scores of war casualties, media coverage of all aspects of horror, and fresh and more detailed revelations of the My Lai massacre had mobilized millions of young Americans to sojourn south to the site of national spotlights, where Revolution might just take place.

The vibrancy of the anti-Vietnam War movement, in all its confrontational colors, would reach its climax that summer. Nixon’s “peace with honor” plan (promoted by his administration as “Vietnamization”) had already failed, and the daily toll of scores of war casualties, media coverage of all aspects of horror, and fresh and more detailed revelations of the My Lai massacre had mobilized millions of young Americans to sojourn south to the site of national spotlights, where Revolution might just take place.

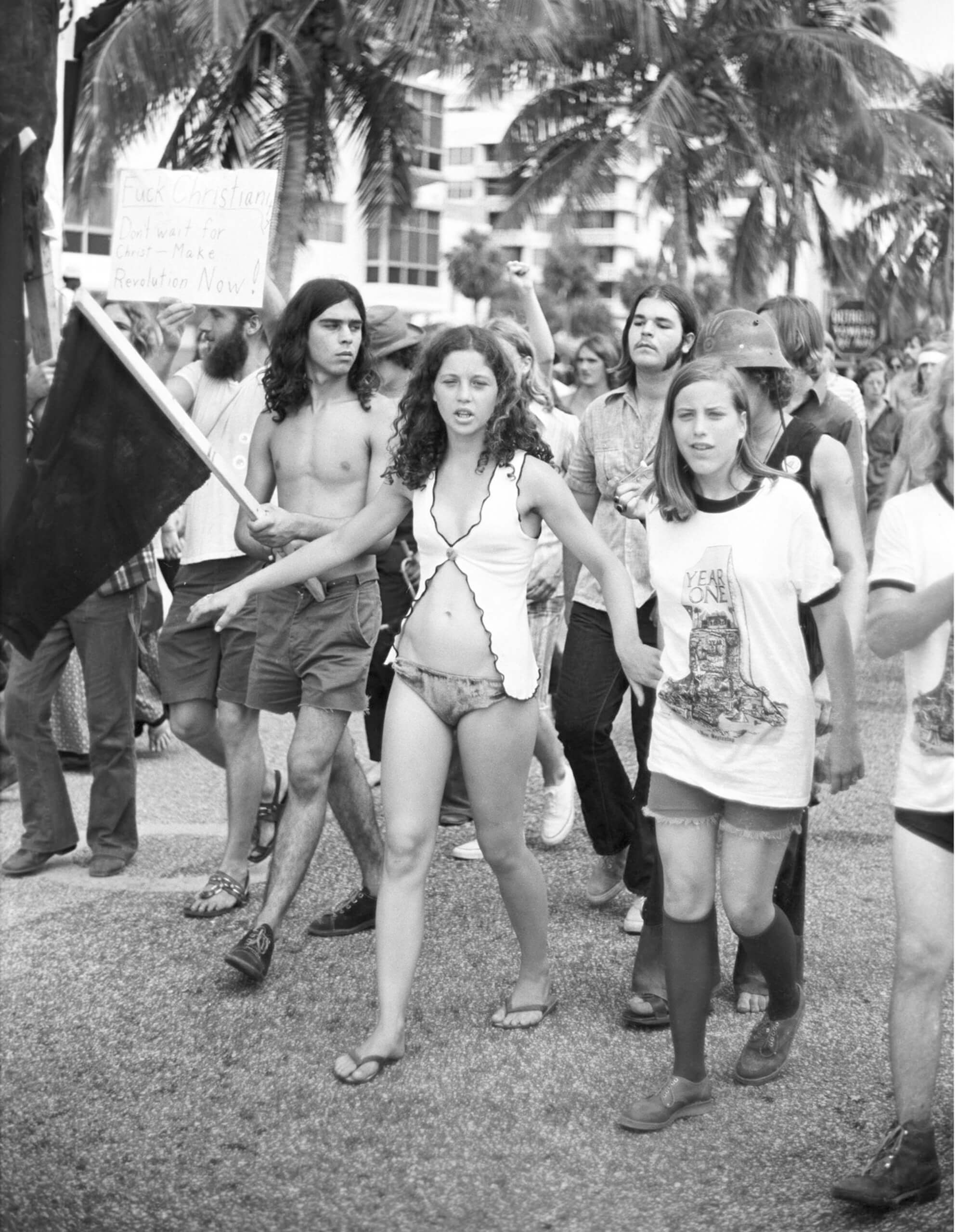

What I saw was always fascinating and sometimes shocking to this 15-year-old. I never knew what to expect from one moment to the next, because there were so many energies pressing into an area of just five square blocks. Often I would just walk around and witness some phases of a marched advance toward the convention building by hippies, “Yippies (Youth International Party),” and other factions which were angrily denouncing the Nixon administration or various aspects of the military-industrial establishment. Signs were nearly always hand painted (“Drop Seeds Not Bombs!” and “Stop Repression”), and I witnessed various aspects of preparations and mobilization.

Timing my entry carefully, I was able to gain access to the building

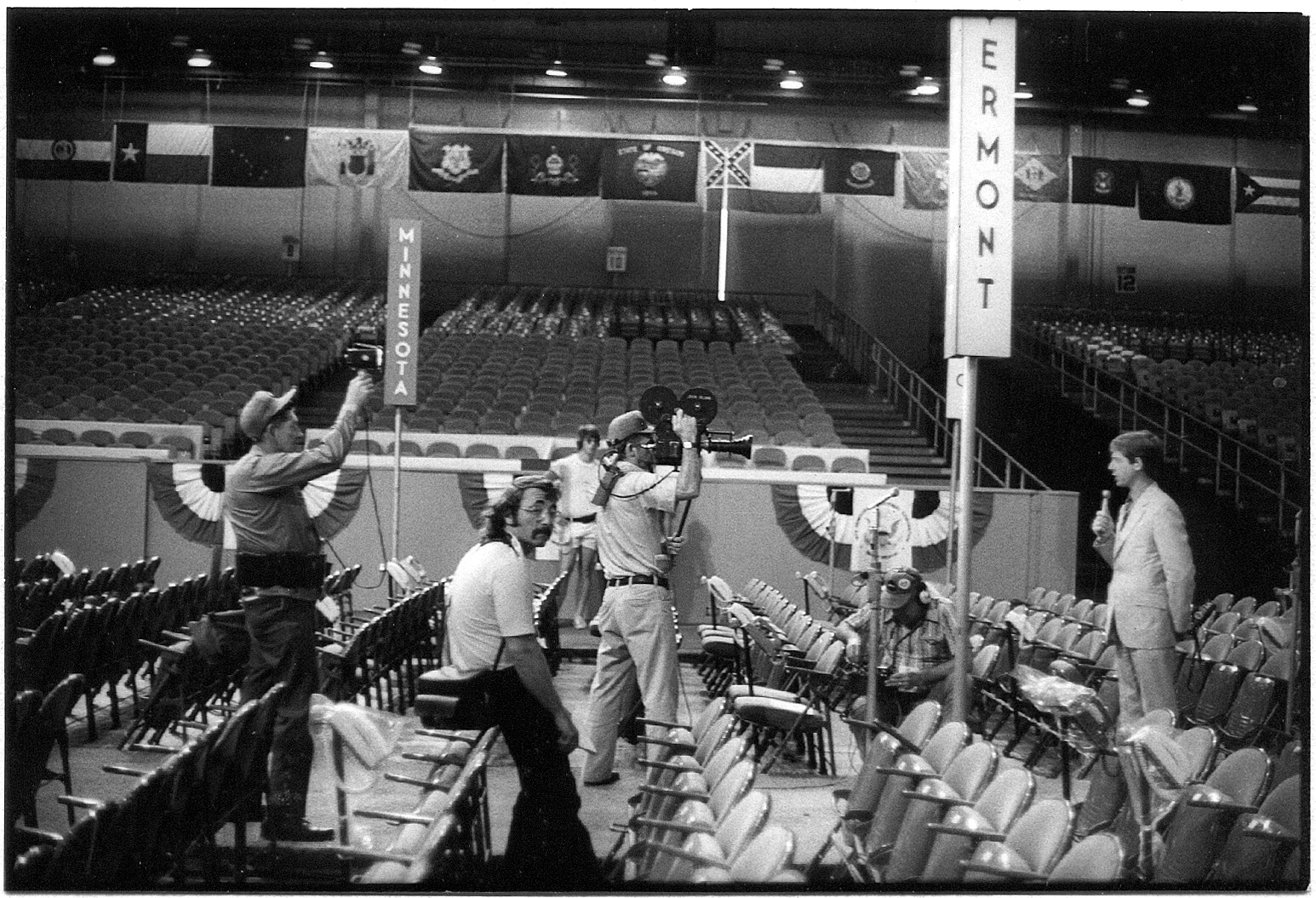

On my initial visit, I arrived a day before the first convention officially opened and wandered toward the convention center. It was well guarded on the front, but when I found myself at the rear of the building, I noticed that buses were able to pull up to a large door and that area was less guarded. Timing my entry carefully, I was able to hide behind a moving bus as it passed through a gate and thus I was able to gain access to the building. Once inside, perhaps it was my camera and equipment bag that gave me the freedom to walk by the police and guards without being detained, but certainly there was far less security than in present times.

I was fascinated by the myriad preparations for the week of conventioneering, the placement of signs identifying each state, the orchestra rehearsing, the parade of reporters making preliminary reports, and the dressing of the main stage. I observed and snapped photos as a spry, young news reporter and his crew filmed his initial on-camera story on the event, and later identified him from his national appearances as television reporter Ted Koppel.

I was fascinated by the myriad preparations for the week of conventioneering, the placement of signs identifying each state, the orchestra rehearsing, the parade of reporters making preliminary reports, and the dressing of the main stage. I observed and snapped photos as a spry, young news reporter and his crew filmed his initial on-camera story on the event, and later identified him from his national appearances as television reporter Ted Koppel.

Virtually everyone there that summer recalled the previous contentious and violent Democratic 1968 convention in Chicago, and both “the police” and protestors were thus anticipating similar confrontations. Certainly, many in the demonstrating faction had also been present in Chicago four years earlier.

I was awed by the energy and creativity of the protesters

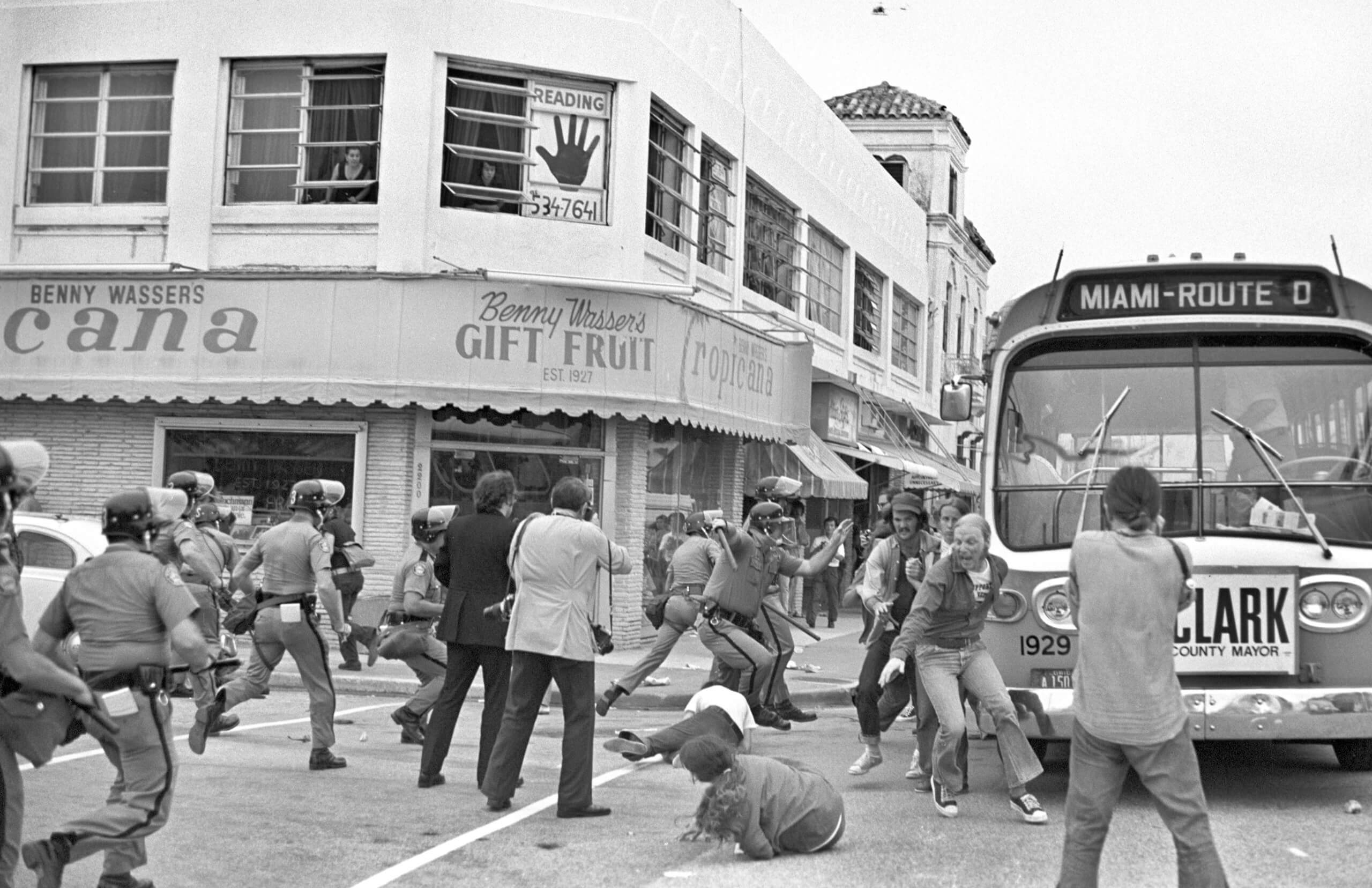

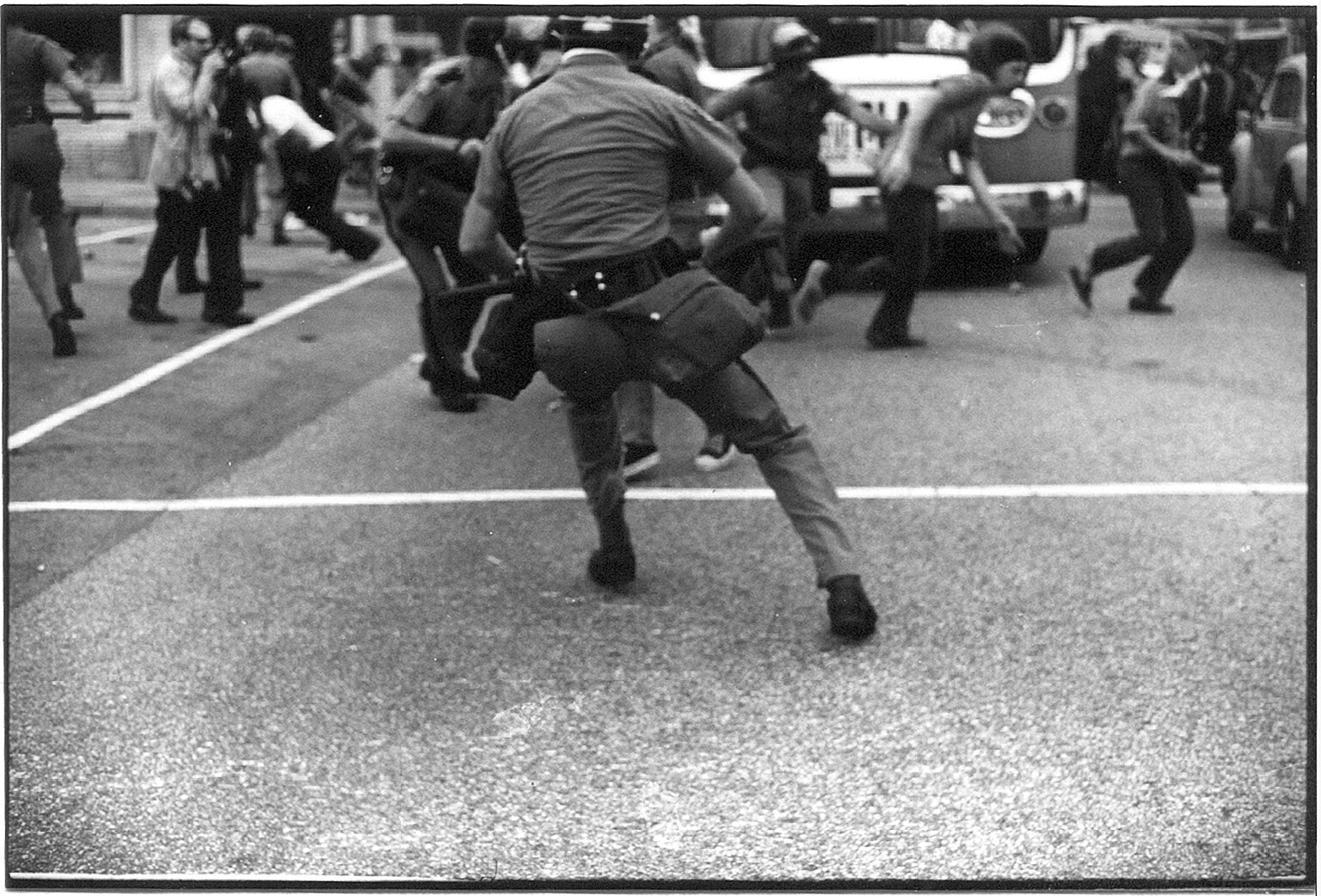

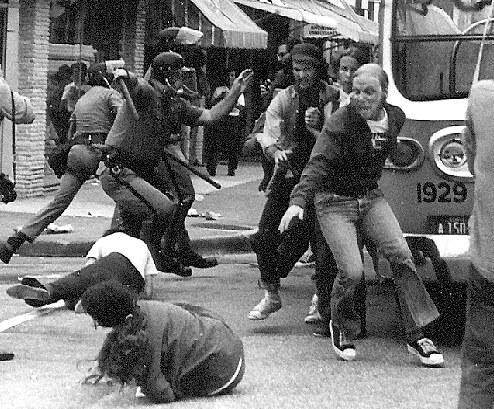

I had seen, first-hand, anti-war demonstrations in New York City when I lived there until 1970, and also saw like confrontations on television, but nothing would prepare me for the first-hand violence, nor the sting of tear gas on my face. Police sirens and the throb of police helicopters added to the high level of tension.

During the various marches and cycles of demonstrating, I observed pitched battles throughout a 20-block area centered on the convention center. In one, in which I was in the middle, protestors tried to take over a city bus but were repelled by city policemen in riot gear. Tear gas charges were fired and I escaped down a street with part of the youthful faction. In another, an angry and shocked crowd formed around a luxury Cadillac carrying delegates, which had plowed through protestors blocking its passage to the convention, injuring various youths and at least one very severely. Perhaps I wasn’t emotionally prepared for the traumatic scene, so I focused instead on a resting hubcap which had hurtled off the car upon impact; my film never revealed the blood and anguish I witnessed.

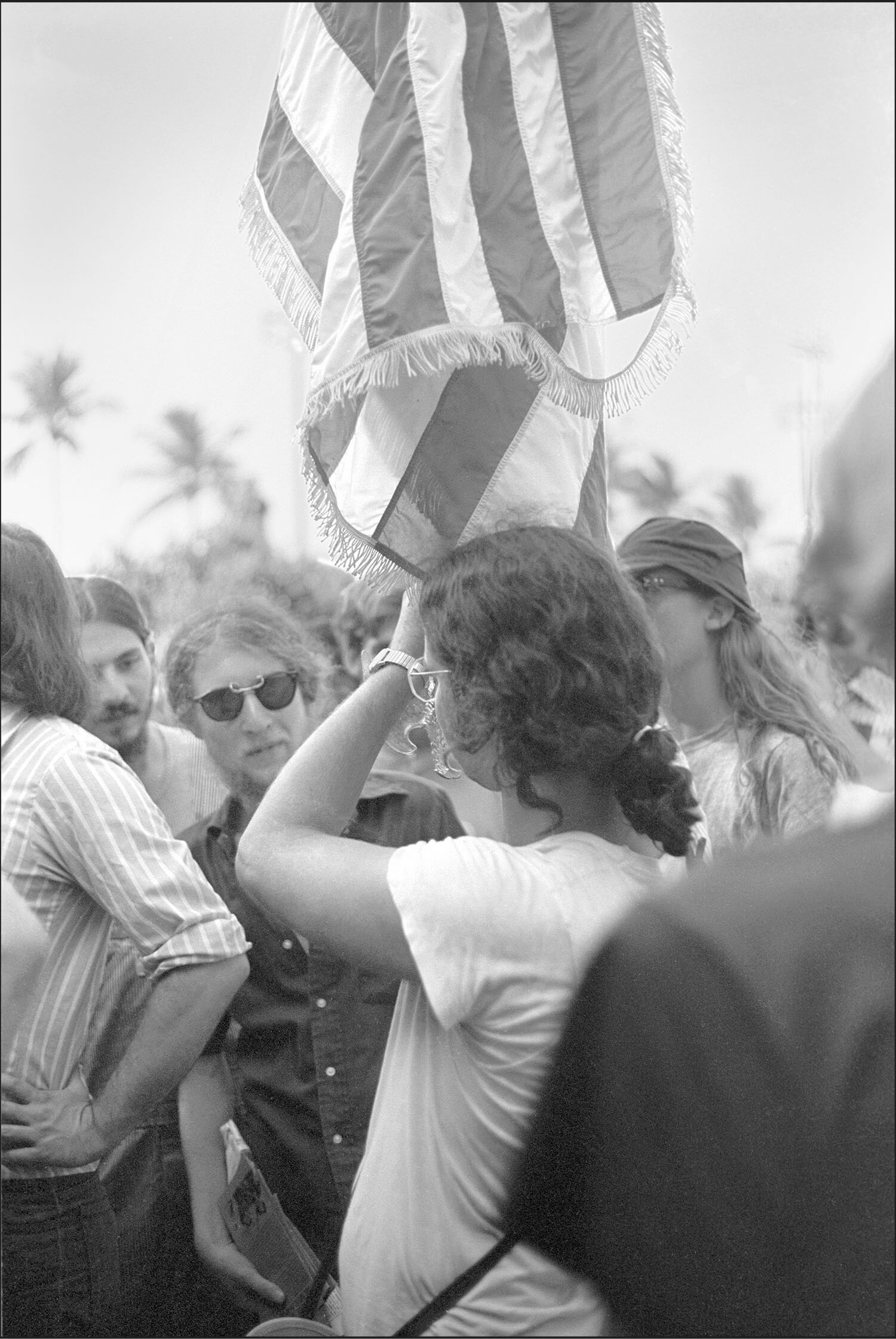

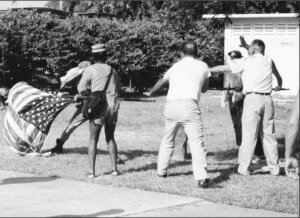

Another confrontation on a later day also impressed me: an anti-war demonstrator found a beautiful specimen of an American flag on a flagpole (probably liberated from a local Kiwanis Club or the like) and proceeded to lead a group of marchers while symbolically holding the flag upside down. Some local residents were duly enraged and one of them, a man of perhaps 70, vainly attempted to wrest the eagle-tipped object from the protestor’s hand; a

Another confrontation on a later day also impressed me: an anti-war demonstrator found a beautiful specimen of an American flag on a flagpole (probably liberated from a local Kiwanis Club or the like) and proceeded to lead a group of marchers while symbolically holding the flag upside down. Some local residents were duly enraged and one of them, a man of perhaps 70, vainly attempted to wrest the eagle-tipped object from the protestor’s hand; a  melee ensued and the older man received a bloody gash on his head.

melee ensued and the older man received a bloody gash on his head.

I was awed and inspired by the energy and creativity of the protestors and especially by the participation of women and teen aged girls there. It was possibly the first time I personally witnessed women in militant leadership positions, yet ironically their cause was pacifism. Women were in the middle of everything, from peaceful and symbolic communication of causes for gender equality, to the most angry and strident exhortations against the war. Many feminists women walked around bare-breasted for either comfort or symbolic effect and would only receive shocked looks from the resident retirees, for at that time Miami Beach was still a sleepy city known mainly for its aged population, kitschy hotels and tourist beaches.

I listened with interest to various speeches by well-known radical leaders such as Abbie Hoffman, and followed reporters and news photographers trailing author Norman Mailer. In this way, I slowly began to learn more about the political situation and better understand the history that unfolded at arm’s length.

The resilience of the protestors and the determination of “The Establishment” repeatedly clashed in a final paroxism of certainty in that summer

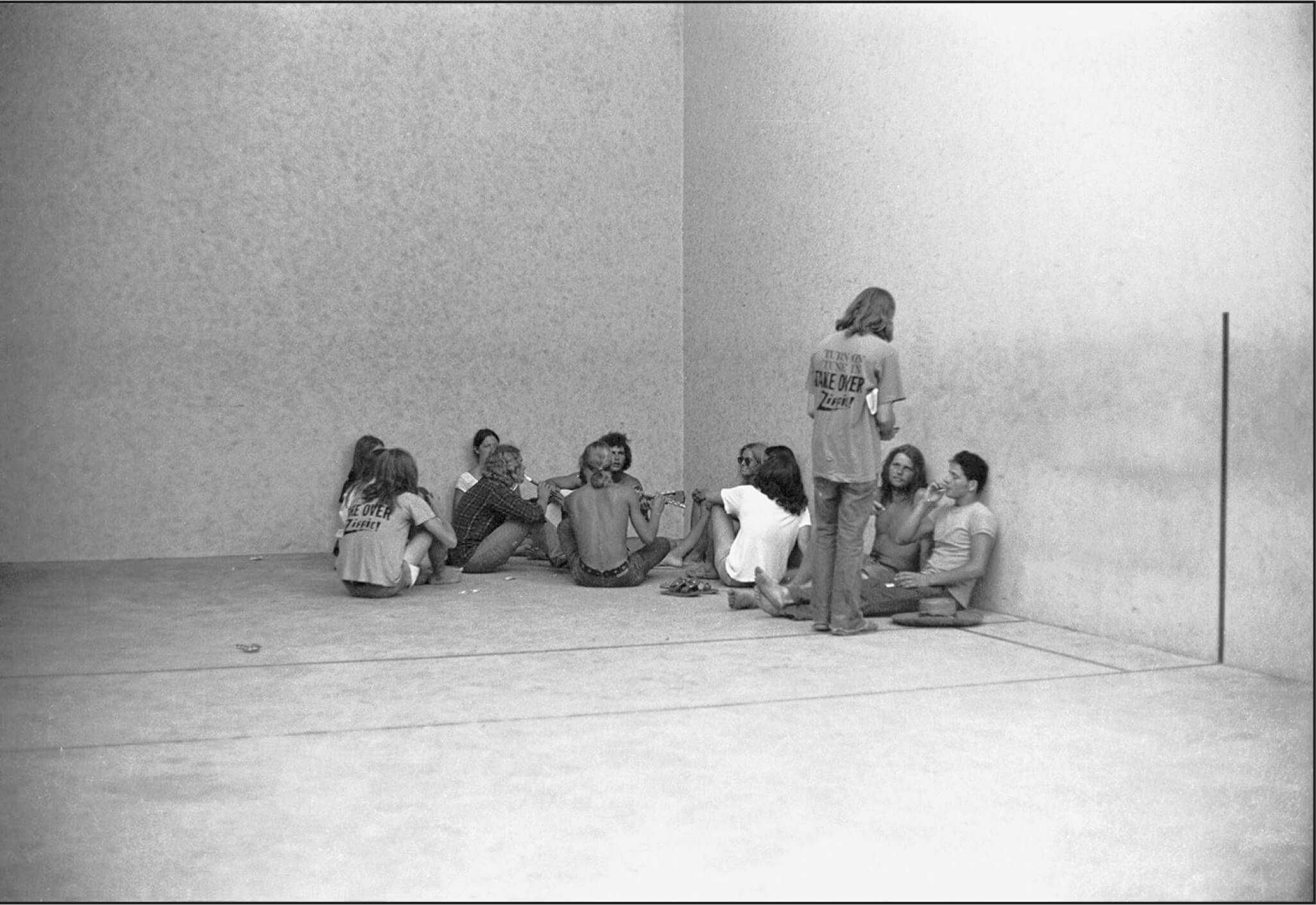

Soon, the tennis courts and ficus groves near the Convention Center became scenes of vigorous debates, tempered to a friendly level by what seemed to me to be the mellow ritual of reefer-sharing. Again, I was familiar  with the concept of recreational drugs from scenes I observed in my earlier years in NYC, but since the youthful visitors were in such large numbers and their preference was primarily a benign marijuana, the police seemed to generally ignore the peaceful smokers and I saw no arrests to break their reverie.

with the concept of recreational drugs from scenes I observed in my earlier years in NYC, but since the youthful visitors were in such large numbers and their preference was primarily a benign marijuana, the police seemed to generally ignore the peaceful smokers and I saw no arrests to break their reverie.

I returned home at the end of each day and developed the film in a darkroom I made out of my bedroom closet. I was yet unfit to execute the film properly, hence the somewhat muddy quality to some of the over- or under-exposed images.

It was a summer of learning for me, about social perspectives, human interaction, the power of people to effect  change. I would see similar scenes of unrest and confrontation in subsequent years, during annual riots at my college, Ohio University (which commemorated the Kent State Massacre) protests against primate experiments and animal cruelty at Emory University, and at anti-American demonstrations in Panama. The summer of ‘72, however, became particularly poignant for me, for I discovered that soon the masses of youth would allow their idealism to wane and by the time I was in college, the focus was less on the world and more on personal stability in the face of rising unemployment and materialism. Although the ‘72 conventions in Miami Beach became one of the last spectacles of the waning days of the Hippies, Yippies and Zippies, I would personally become involved in the anti-apartheid campaigns, political races, the environmental and global climate change causes, and scores of animal rights demonstrations. But it would be more than a quarter-century until the revolutionary fervor of the 60s and early ‘70s would even remotely approach the galvanizing energy of the anti-Vietnam war era, during protests against the domination of world bankers or the Iraq War. To my utter disappointment, I spent much of my college years relegated to small events promoting social amelioration that were deemed either too idealistic or irrelevant by the majority of my own generation of teens.

change. I would see similar scenes of unrest and confrontation in subsequent years, during annual riots at my college, Ohio University (which commemorated the Kent State Massacre) protests against primate experiments and animal cruelty at Emory University, and at anti-American demonstrations in Panama. The summer of ‘72, however, became particularly poignant for me, for I discovered that soon the masses of youth would allow their idealism to wane and by the time I was in college, the focus was less on the world and more on personal stability in the face of rising unemployment and materialism. Although the ‘72 conventions in Miami Beach became one of the last spectacles of the waning days of the Hippies, Yippies and Zippies, I would personally become involved in the anti-apartheid campaigns, political races, the environmental and global climate change causes, and scores of animal rights demonstrations. But it would be more than a quarter-century until the revolutionary fervor of the 60s and early ‘70s would even remotely approach the galvanizing energy of the anti-Vietnam war era, during protests against the domination of world bankers or the Iraq War. To my utter disappointment, I spent much of my college years relegated to small events promoting social amelioration that were deemed either too idealistic or irrelevant by the majority of my own generation of teens.

At age 15

The experience of viewing the activities and milieu at the ‘72 conventions through my camera viewfinder did form the basis for my career as a magazine photojournalist, advertising photographer and my lifelong artistic passion for documenting peoples of the world. It taught me how miraculous a still image can be in capturing both the larger context and fascinating details of time and place. The resilience of the protestors and the determination of The Establishment repeatedly clashed in a final paroxysm of certainty in that summer, and I was forever changed as a person and a photographer.

I learned a lot reading this blog. It was well-developed and written in a professional sophisticated fashion. The photos added to the story. I look forward to more from this writer.

The ardent zeal of protesters always impresses me. The fact that so many were willing to risk attacks of all kinds – and even arrests – is a profound thought. I admire the variety of scenes you were able to capture, such as the shot from inside the convention center, and the flag scenes.

Thank you Ed, I look forward to more comments from you!